Manufactured landscapes. Infrastructure and nature’s relationship as an artificial sociotechnical entity is a fascinating undertaking. However, we should not fall into simple human/nature binary assumptions. Infrastructures do not separate humans from their environments. Instead, they overlap as new or different assemblages of human and non-human nature. Infrastructures allow us to understand the construction of our environment. However, they can’t be fully naturalized either; they are manufactured landscapes (Zeller, 2017). According to Neil Everden, if the concept of nature is a social construct, we might be confusing nature with threats of pollution. Ecological infrastructure (re)produces[1] the burden or stress we experience in terms of socio-ecological or political power (Everden, 1992).

Environmental citizenship. At a planetary scale, techno-politics and ecological politics are inextricably complex. Examples vary from the Pana Canal’s water management and forest preservation tactics to interstate roads and highways in the US and many other water management projects built in India and China, including dams, canals, and hydrological distribution systems. Timothy Mitchell refers to projects at this scale as “capital infrastructures .”He proposes that infrastructure is a politics of nature produced in infrastructure (Mitchell, 2014). As Everdeen also implies, it has a social use, and finally, we experience nature via the infrastructure we build (Everdeen, 1992).

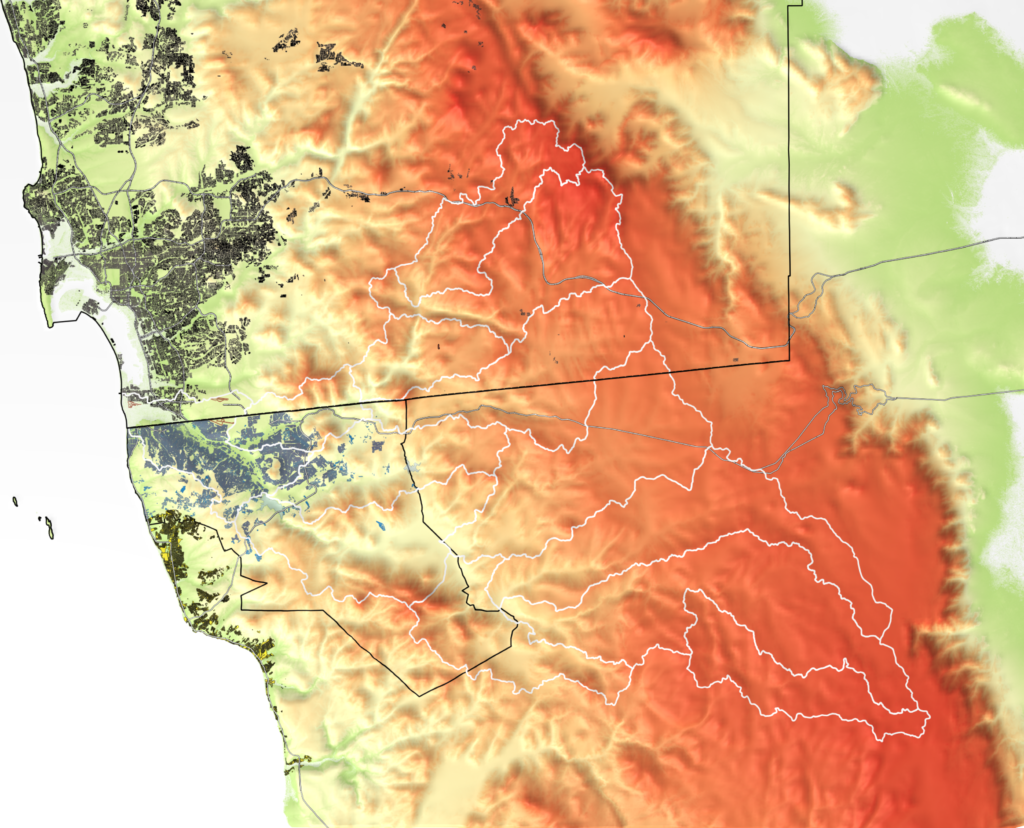

Nature, therefore, cannot be assumed as background. The possible interpretations of the study of nature and infrastructure set up a series of Large Technological Systems (LTS). According to Ashley Case, LTS systems can also be part of political struggle. The US/Mexico border acts as a political divide and a sociotechnical and militarized infrastructure. The wall separates two nations and two different sociocultural systems and acts against ecological preservation efforts. The border wall transgresses sensitive ecological reserves that are part of a shared watershed between San Diego and Tijuana. It impedes traffic of human (undocumented) and more-than-human[2] entities such as seeds, plants, mammals, and reptiles, that are part of the pristine ecosystems shared by the two countries. The physical metal structure of the border ends in the sandy beach of Tijuana and plunges into the ocean, demonstrating its global hegemony thru techno-environmental politics. The US national public has seen the wall as a determent infrastructure. In academic studies, including urbanism, urban geography, or infrastructural studies, the wall has been subjected to harsher criticism for its ecological and geopolitical imperialism and as an act of urbicide[3].

Sophia Stamatopoulou-Robbins recounts that electricity systems, landfills, and water infrastructure in the Israel and Palestine border are power devices. However, infrastructure could bring together interests and individuals across political boundaries, demonstrating a post-national environmental commitment (Stamatopoulou-Robbins, 2014). Therefore, these border infrastructural systems deployed between US/Mexico can be devices for cooperation instead of separation.

For urgent binational cooperation, a case in point is the All American Canal that transports water from the Colorado River to the US southwest region and into Mexico. The city of Tijuana gets most of its water from the canal and seepage from the ground of the channel used to fill natural reservoirs that served the agricultural community of the Mexicali Valley. Recently, the US decided to line the canal’s floor with concrete due to the region’s sustained drought cutting off Mexican agricultural lands from the water necessary to grow their crops. Ironically, many of these agricultural products produced in Mexico are exported to the United States. Could there be an environmental citizenship claim over national ones, allowing both sides to share the resource equally? (Stamatopoulou-Robbins, 2014)

Mobile Umwelt. Mobility in many border cities along the US/MX border is dominated by the private automobile for two reasons: Many of the cities along the border developed their mobility infrastructure during the 20th century, roadbuilding became the main form of connectivity between binational urban and rural areas. Second, the export of vehicles from the US inundated the Mexican market with low-cost second-hand cars. Roads have become vehicles of modernity that ‘form us as subjects’ mobilizing ‘after and the sense of desire, pride and frustration’ (Barua, 2021) (Larkin, 2013).

Mobility has shaped socio-economic relations of power (Monroe, 2014). This phenomenon created a social polarization where those who owned used vehicles with California plates were considered economically poor and from different social statuses. At the same time, owners of new cars with Mexican license plates were viewed as middle or upper-class citizens that could afford a car from a local auto dealership. In the same way, municipalities built roads with superior techniques in upper socio-economic areas and working-class communities did not have paved roads or were of inferior quality (concrete vs. asphalt).

The infrastructure of circulation, such as road networks, impacts more-than-human entities. Roads have become habitat corridors modifying an organism’s flow pattern throughout our global geography. Motorways can also enable the intermixing of habitats that were once isolated or inhibit motion in areas that were natural distinct corridors. From termites traveling for thousands of kilometers in shipping containers to macaques in southern India that gravitate towards roads to get food from passing vehicles, the architectures of circulation are the enmeshment of animals and infrastructure. The material politics of roadbuilding and etho-geography can develop a political ecology of infrastructure, one attentive to animal mobility beyond human-centered environmental impact assessments (Barua, 2021).

Works Cited

Barua, M. (2021). Infrastructure and non-human life: A wider ontology. Progress in Human Geography, 1-23.

Everden, N. (1992). The Social Creation of Nature. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology 42, 327-343.

Lefebrve, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Mitchell, T. (2014). Life of Infrastructure. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 34 #3, 437-548.

Monroe, K. V. (2014). Automobility and Citizenship in Interwar Lebanon. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 518-531.

Stamatopoulou-Robbins, S. (2014). Occupational Hazards. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. 34 no. 3, 476-496.

Zeller, T. (2017). Aiming for control, haunted by its failure: Towards an environtechnical understanding of infrastructure. Global Envrinoment 10 no.1, 202-228.

[1] I like to use the term produce [man] rather than create [nature] as Henri Lefebvre argues that nature does not produce. “And, yet nature does not labour: it is even on of its defining characteristics that it creates. What it creates, namely individual ‘beings’ simply surges forth, simply appears” (Lefebrve, 1991).

[2] Laura Harjo in her book Spiral to the Stars: Mvskoke Tools of Futurity, mentions that the Mvskoke people refer to non-human entities as more-than-human.

[3] Urbicide is defined as “violence against the city”. The term was first coined by Michael Moorcock in 1963