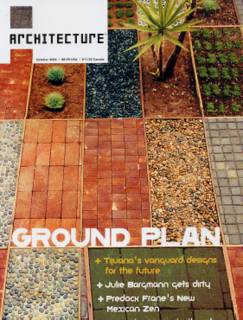

En la revista Norte Americana “Architecture” La Nueva Tijuana y La Ciudad Fea comparten espacio. Octubre 2004.

OCTOBER 12, 2004 — “Tijuana is the ugliest city I have come to know, a filthy city,” René Peralta writes online of his birthplace. “In its urban condition, Tijuana is also deformed. But this deformity is what makes it interesting.”

An architect, teacher, and frequent blogger, Peralta is one of a band of emerging Tijuana designers, artists, and academics who embrace the chaos and friction of a city exploding with migration, development, and vibrant but clashing cultures. Small affluent neighborhoods dot the city’s old center and the Pacific coastline, while in every other direction thousands of shacks bereft of electricity and running water cling to steep, barren hillsides. As a design laboratory, Tijuana is as provocative as it is dysfunctional.

Peralta’s firm, generica arquitectos, rents a small office a short walk from the noisy, frenetic port of entry connecting San Ysidro, California, and Tijuana, where an estimated 7 million pedestrians and 34 million vehicles cross la linea each year. Intrepid street vendors, window washers, and begging children careen toward Mexicans and Americans in SUVs, F-150s, and jalopies creeping north. The circus atmosphere, dampened since September 11, 2001, has always been tinged with desperation.

Peralta is passionately rooted in Tijuana, where his family has lived and owned businesses and property for 80 years, a history few other local families can match. He and his forebears have watched generations of transients treat Tijuana as a mere steppingstone to the United States. In calling it “the ugliest city,” Peralta applies a concept he learned at the Architectural Association in the mid-1990s: Ugliness is born of excesses and absences. For him, Tijuana is both extremely stimulating and vexing.

Runaway Development

Peralta’s city is 17 miles south of San Diego. “Psychologically, culturally, socially, we have always had the world’s richest country right next to us,” says Miguel Robles-Duran of rhizoma, another young Tijuana architecture firm. “Not only that, we’re next to the most expensive state and one of the most expensive cities in the United States. Mexicans want to live like Americans, so developers here copy San Diego [housing tracts]. What’s worse, they make bad copies.”

Perhaps this view helps explain why Nueva Tijuana, the unofficial name for the city’s sprawling eastern flank, seems as alarming as the shantytowns to some observers. Gated residential tracts sporting slick marketing signs are big business.

Private developers are rushing to meet an unprecedented housing demand from migrants lured by jobs at maquiladoras, the border-hugging assembly plants owned by foreign companies. This latest boom is different: Mexican professionals have joined the throngs of unskilled workers, and some of these new arrivals plan to settle here permanently.

The city’s current population surge (estimated at 1.2 million in Mexico’s 2000 census, though experts say that figure could be 500,000 higher) is not expected to slow down any time soon. In response, the Baja California state government plans to create 50,000 mass-produced housing units this year and 60,000 in 2005, primarily financed by federal loans and built by private entities. Tijuana’s master plan places these housing tracts near the maquiladoras and stretching into the city’s eastern outskirts.

In researching a book Peralta is coauthoring on Tijuana, he was astonished to learn that nearly half the city’s population now lives in Nueva Tijuana. Housing construction gobbles up more than five acres of land per day, according to local city planners. Some of these developments crudely quote Spanish-style details, such as red-tile roofs and arched windows. But these cartoonish embellishments are too expensive for most Mexicans, so much of Nueva Tijuana is now sprouting flat-roofed, introverted masonry compounds with massive gates.

Gated communities are a justifiable response to Tijuana’s high crime rate, Robles-Duran says, which ranges from car theft to neighborhood shootouts. With high walls and locked gates, developers are providing security—along with utilities, schools, and paved roads—that the impoverished government has failed to deliver.

Most of the new tract homes sell for $25,000 to $40,000, but for just $15,000 a family can squeeze into a micro casa, a boxy, attached unit of less than 300 square feet. Suddenly, a maquiladora line worker earning $200 per month might be able to afford one of these tiny, one-bedroom homes, but ownership comes at a psychological price.

“People are going to go mad” in them, argues Peralta, who is also part of Operativa 4, an activist group of designers and artists who hope to infuse humanism and design expertise into this raging phenomenon. However rudimentary they may be, shacks can be expanded at will to accommodate extended families, but most micro casas are literally boxed in.

An Uphill Battle

“Architecture is a luxury here,” laments Robles-Duran, who recently left Tijuana to study at the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam. He doubts he and his architect wife, Gabriela Rendon, will return, except to oversee the completion of two private homes he designed that are now under construction.

Other young architects share Robles-Duran’s frustration with the city, yet they remain committed to easing its growing pains and elevating its substandard housing. Peralta, for example, hopes to find a new client to revive generica’s 2002 design of a five-level, modular apartment tower called the Mandelbrot Building. Commissioned (but not built for lack of funding) for a standard-sized urban parcel, it can be reconfigured for different sites. The Mandelbrot could become a mass-produced alternative to Nueva Tijuana’s ominous, two-story housing tracts.

If he could, Peralta would halt the city’s runaway expansion and redirect the massive building frenzy into high-density, high-rise housing near work, transportation, and cultural centers. He and his peers might stand a chance when Tijuana’s old core is redeveloped, a priority of its city planners. But the architects’ chances seem slim in Nueva Tijuana, where thousands of families can buy their first homes and the bulldozers never sleep.

Ann Jarmusch is the architecture critic at the San Diego Union-Tribune.