This week Bryan Finoki posted on archinect a link to a very interesting article concerning the future makeover of Havana’s malecon (click here), via a studio project directed by Nicolas Quintana professor at Florida International University. What is interesting to me is that the projects -32 mock ups- are intended to demonstrate the future of the malecon and nearby areas of the city, as ”a wealth of ideas, not definitive solutions” to rescue and protect the city of Havana once democratic change takes hold on the island” (Cansio 2007). My concern lies in their view of democracy solely based on covert operations for urban renewal and autocratic design methodologies. As the article explains, it seems that in order to collect site data of contextual conditions they have engaged in spy tactics using informants inside the island, as well as military style strategies via satellite imagery.

“For guidance, the architectural study will be based on the study of geographical plans of the city and information culled via satellite, complemented with recent photos of the facades of buildings and entire neighborhood blocks in Havana.

For the historical data, they have scoured copies of the Archives of the Indies, Cuba’s national library and the University of Havana, and they have numerous anonymous collaborators on the island” (Cansio 2007).

I thought that any democratic development should promote equal voice to all members while discussing the future through a transparent and egalitarian process. It might be ( I have not seen the actual projects) that these future visions of Havana only promote a simulated democracy or a calculated plan for globalized urbanism.

Quintana explains that their plans and projects are inclusive and they wont pretend to impose their vision on the “architects and urban planners that will assume the revitalization of the city,” (Cansio 2007). Who will assume this responsibility? It almost seems that they have selected to negate participation of the people for whom they are designing until they find the chosen one (s) to carry out this “democratic” redevelopment operation. At the same time while being inclusive and pursuing democracy they will “refuse to cooperate with the destroyers of the Cuban way of life,” (Cansio 2007).

Yes, the Cuban way of life filled with great music, gambling and other illicit acts prohibited in the US, a “playground for the rich and famous” as the Cuban writer and biographer of the mafia in Cuba, Enrique Cirules explains. It was the era of great modernism in Havana, like no other in the world with works by Phillip Johnson, Sert, Neutra, Albini and other prominent modernist (Luis 2000). Yet, this modern museum of a city was erected during the reign of the Batista-mafia regime backed by the US government, a mafia that was driven out in 1958 by guerrillas from the Sierra Maestra. US mafia groups, that without Batista, or his political-military leadership, could not prevent the entrance into Cuba of the powerful New York Mafia families with whom they had been at war in 1957, or prevent the dispersion of their lucrative business deals in Havana (Cirules 2004).

The last time I was in Havana (2003) I walked for hours on the malecon, sipping rum and watching people gather throughout its long and winding extension, pockets of social groups had appropriated their sections and as I moved along I experienced diversity and public space. If I remember correctly the malecon did not need to be redesigned. There were some renovation projects that began to be seen along the nearby streets. My friend in Havana, Alberto Faya, had taken a group of us to see his restoration effort in Boyeros, a whole town designed in Deco style. Surprisingly Havana was slowly restoring its buildings and its future in the most imaginative way they could and how they have always done everything since the big spenders left the country to Miami.

Now they (Miami) want to revive a city they might not understand anymore, envisioned through memories and with the help of the US mass media they have been able to see a new yet filtered and artificial picture. Quintana himself has not been to Havana since 1960 (Cansio 2007).

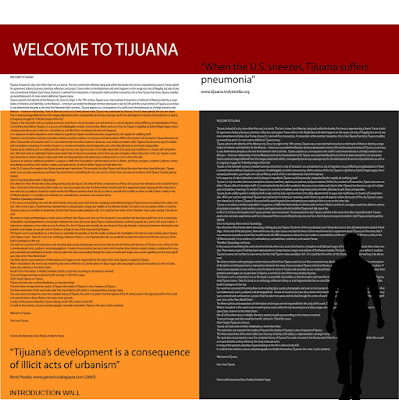

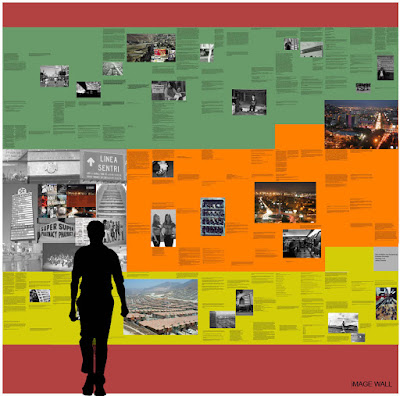

Cubans lived the splendor of a non-ideological modernism and once the rug was swept from their feet they embarked into a reality that many societies are in the wake of experiencing. In the same manner Rem explains about Lagos: Havana is not catching up with us. Rather, we may be catching up with Havana. Havana reminds me of Tijuana in the sense that disparity has not blinded these two sister cities in navigating toward their own future, and whatever the outcome is – survival or demise – the world, might, just might, learn something about survival and re-invention.

Cansio Isla, Wilferdo. Makeover Designed for Havana’s Malecón,. El Nuevo Herald 12/23/2007

http://www.miamiherald.com/news/americas/story/355563.html

Cirules, Enrique. The Mafia in Havana. Ocean Press, NY 2004

Luis Rodriguez, Eduardo. The Havana Guide, Modern Architecture 1925-1965, Princeton Press. NY 2000

Koolhaas, Rem. The Harvard Project On The City, ‘Lagos’ in Mutations, Actar, Bordeaux 2001.

Note: I am very interested in seeing the projects so that I can comment on them more objectively, for know this response is directed to the Herald’s story and its presentation of the subject.