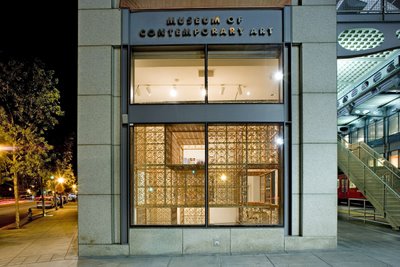

Con la prisa de terminar la instalación de Genérica para la exposicion, Strange New World en el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de San Diego, que inicia el 20 de Mayo, no me queda tiempo para postear algunas ideas. Pero por lo pronto les dejo el texto del catalogo de dicha expo ya antes posteado en español, lo paso en ingles con algunas postales y discos de mi colección.

Debunking Utopia: The Vicissitudes of Tijuana Modernism.

Rene Peralta

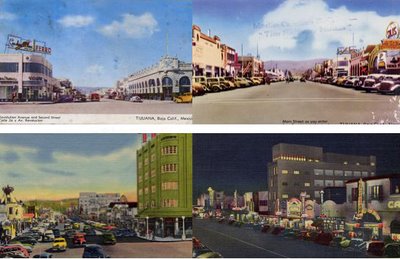

As the concept of cities are redefined, urban centers are in a state of entropy. Downtowns are becoming vertical suburbs, or undergoing a thematic renaissance of simulated street attractions. Downtown Tijuana, El Centro, has had its share of thematic attractions since the days of prohibition. Avenida Revolución, the main tourist party-strip, has become the sole urban experience for visitors to Tijuana. Curio shops, bars, ”zonkeys” (donkeys used to take souvenir photos with tourists), and other hybrids of commercialism and folklore occupy and perform in buildings that conform the scenary of a Latin house of mirrors where everything that is supposed to be grounded floats, life is depicted in satin, and miniaturized in plaster. Yet, to the west beyond old Olvera Street, a series of anonymous buildings exists, veiled expressions of modernity and border culture that intended to drive Tijuana into the paradox of universality and regionalism.

Since the execution of the ill-fated Plan of Zaragosa—a copy of a city beautiful model executed somewhere in the mid-western United States—these bastards of modernism have existed as the apotheosis of the knockoff, “architecturesque” designs. Pseudo-modernist or provincial habitational machines, utopias or junk space, buildings that in the past were part of the city’s “good life” and an obscure, idiosyncratic modernist avant-garde are now artifacts, ghostly reminders of a lost downtown. However, they still play a role in the city’s daily urban effervescence, and their full splendor is still visible in the numerous postcards sold in the shops of Avenida Revolución.

These pseudo-modernist relics act as lattices correlating with pedestrians, neon signs, the mini buses called Calafias, street vendors, and all the other programmatic manifestations that El Centro invents. You find them on corners, as full blocks, or fill-in constructions, often invisible to the naked eye, hiding behind layers of paint, advertisement, and neon. Only a trained or nostalgic architect would find the buildings among all the glitter. Because most of the buildings were erected between 1930 and 1960, their designs are an eccentric and hybrid arrangement of Art Deco motifs with a high modernist sensibility. The buildings feature a modernist repertoire and an eclectic mix of utopian idealism: Corbusian free facades and garden terraces as well as Gropius glass corners, all combined with imitation Mallet-Stevens grand interiors and other spurious combinations.

The Calimax building on 5th Street was the first major store of the local supermarket chain; with its soft round corners and the streamlined effect of its bands, as well as the curvy font in its signage, it is one of the purest Art Deco-ish buildings in town. Today it still functions as a grocery store, and its upper floors are used as office space. Further north on 5th, the Downtown District Building is an interesting take on Corbusian principles, with its roof garden and strip windows. The building sits proudly on a street corner and, oddly enough, it is this site condition, which necessitated the chamfered corner, which denotes its status as an architectural phony.

Signs, air ducts, and recently added appendages penetrate these buildings’ facades acting as life-support. The buildings are monuments to their own demise in a forgotten downtown. And yet, they seem to be in a mode of perpetual recycling instead of decay, as we might expect. They function as artifacts, as Aldo Rossi would define any construction that played a role in contributing to the collective memory of place.[1]

A shoestore named Zapatería Diseños Variety operates from a white box building on Avenida Constitución that boasts an appliqué of advertisements and graffiti that declare the “variety “of functions found in the building’s interior. Situated in the middle of the block, the building is practically invisible from the street due to the large awning that blocks its view and creates a spatial disjunction between circulation and transportation at street level, as well as with the building’s interior program. The elegant glass block corner unconsciously alludes to those found on Bauhaus style buildings.

Modernism was never a part of a national ethos in Tijuana, as it was in other cities in South America, where it embodied a project for the future. Only the tropical modernism of the city of Havana might compare to Tijuana’s, given that the buildings are in reuse and were the product of the economics of tourism and casinos built in the Batista era.

The national architectonic ethos would arrive in Tijuana from Mexico City during the 1970s and ‘80s with a patriotic modernist brutalism of efficient cast concrete construction and labor-intensive chiseled facades—a resurfacing intended to bring out the coarseness and grain of the aggregate, emulating a nostalgic building craft. The Centro Cultural Tijuana is the foremost example of this national modern philosophy. It is a building contextualized in a seamless fashion, without the author’s consent..Like the city’s other monuments of deceitful origin, CECUT is seen as a “knock–off,” specifically of Étienne-Louis Boullée’s Cénotaphe de Newton.

Tijuana’s urban center was stripped of its political, religious, and financial cores, along with their encompassing ideologies, by the creation of the Zona Río and its intention to Mexicanize Tijuana. A center to some, and a periphery to others, psycho-geographic rather than geographic, the origin of Tijuana is always half-baked and transformed while in the midst of becoming. Today, the downtown economy is made up of clusters of restaurants, small businesses, and pharmacies, while at night, bars, strip clubs, and massage parlors cater to the imagination of the forbidden. El Centro was once part of a vision of a city beyond border rhetoric, despite its interesting proximity to the border. Today, it is the urban space of desire.

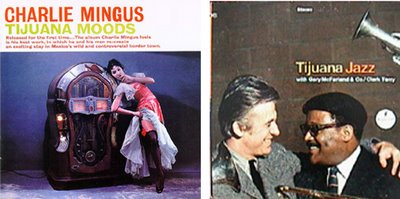

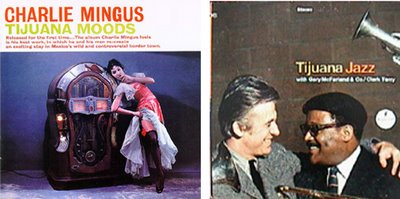

Downtown was the place where cabarets featured big bands, jazz quartets, and other musical manifestations rarely seen today. It was home to the “good music”—as a well-known cantinero who tended bars at Aloha, Club 21, Frenchis Bar, and currently at the Coronet Piano Bar—once exclaimed. Yes, Tijuana has been a jazz hub since the 1920s. Musicians from New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego crossed the border to play a gig, have fun, or drown their sorrows at the local bars. The famous jazz bass player Charles Mingus dedicated an album to the city, “Tijuana Moods,” a musical orgy of jazz, rhythm, and musical representations of city sounds and verve.

All the music on this album was written during a very blue period in my life. I was minus a wife, and in flight to forget her with an expected dream in Tijuana. But not even Tijuana could satisfy—despite the bullfight, jai alai, anything that you could imagine in a wild, wide-open town.[2]

Born in Nogales, Arizona, and raised in Watts, Mingus died in Cuernavaca, Mexico, and was haunted by Tijuana’s dislocated border as a dystopic city in a phantasmagoric country.

The music of El Centro became an international phenomenon, creating the “Tijuana bandwagon” as it was called when someone wanted to recreate Latin sounds heard in the many bars of the city. The scene was so popular that in the 1930s the city of Baltimore had a jazz joint called Club Tijuana. In 1921, Jelly Roll Morton obtained a visa to work in Tijuana and composed the Kansas City Stomp and The Pearl, titled after a beautiful waitress named Perla who worked at the Kansas City Bar. Gary McFarland and Clark Terry recorded their “Tijuana Jazz” record in1965, and between 1962 and 1968, Herp Albert won six Grammies with his famous band Tijuana Brass.

Downtown is where music and urban living were one. The Escamilla Photography Studio, located on 2nd Street, boasts an early modernist interior within a grandiose and theatrical space. “The studio was designed as a scenic space to show off the artistic qualities of the architecture,” Carlos Escamilla explained describing the building his father built between 1950 and 1953. “Patrons would ‘dress up’ in evening wear as if going out for a night on the town and walk through the double doors to have their portraits taken.” Today the studio’s upper floors function as storage space for bygone memories recorded on celluloid, and most of the portraits Escamillo takes are Polaroids of walk-in customers.

Walking the streets of El Centro you become conscious that Tijuana desired at one time to be an ordinary city. The singularity of its buildings and the ill-fated Beaux Arts planning were the spirit of Tijuana’s cultural zeitgeist before the shantytowns, cartolandias, junk space, and other ad-hoc patterns emerged as the contemporary urban and artistic paradigms. Today the buildings are still modernist, although minus the lifestyle; they have incorporated themselves into the pluralities of the post-modern city.

As you make your way through sidewalk vendors, street merchandise, shoeshine stands, and pedestrian traffic, movement unfolds. El Centro is a “practiced place” where the entire urban space is experienced through the multiple layers of constructions and events. Fake, albeit ill-conceived or not, the buildings of Tijuana’s downtown are part of a notion that fluctuated between the universal and the local, emerging as a cultural product difficult to surpass, even by the contemporary conditions of border phenomena.

[2] Mingus, Charles. Tijuana Moods LP, 1962 RCA Records, Jacket Cover