Este Blog Cumple 10 Anios – A celebrar con mi texto que se publico en el Libro del 30 aniversario del Centro Cultural Tijuana.

La historia de una Bola

René Peralta Ramírez

¿Qué es la imagen o cómo se construye un símbolo arquitectónico? La arquitectura es parte de un imaginario común que crea vínculos entre el espacio social y físico. La producción de los símbolos es una labor muy diferente a la producción del objeto tectónico situado en el espacio de la ciudad. Los arquitectos producen objetos concretos basados en lógicas cartesianas, sin embargo, la producción de símbolos urbanos no es sólo producto del arquitecto. El espacio social de la ciudad se produce por medio de la interrelación de ideas, vivencias y experiencias de los ciudadanos, que con el tiempo producen e identifican los símbolos dentro de la misma; sin embargo, el quehacer de la arquitectura se considera un acto político que produce obras dentro del espacio físico de la ciudad (o absoluto, como dijera David Harvey). Estas obras están basadas en ideologías abstractas de la forma (teorías), dentro de la disciplina o de una visión idealista del mundo en que vivimos: simetría bilateral, ejes, órdenes clásicos o superficies.

Históricamente, la producción de la arquitectura como símbolo, invariablemente ha estado ligada con percepciones cualitativas: los caminos, los cerros, montañas o el cosmos; vinculadas con acontecimientos cíclicos: tormentas, producción agrícola, eclipses, etcétera; y después connotada por medio de la representación abstracta de la geometría arquitectónica. Fue en el siglo xx cuando se promovió la disolución de la carga simbólica en la arquitectura por ideologías de nuevos flujos e intercambios sociales que produjeron las economías de un mundo universal e industrial, y que al final originó una arquitectura racional. Como explica Manfredo Tafuri, a principios del siglo xxse inició el proceso de formación del arquitecto como el ideólogo de una nueva sociedad universal y antihistórica.[1]

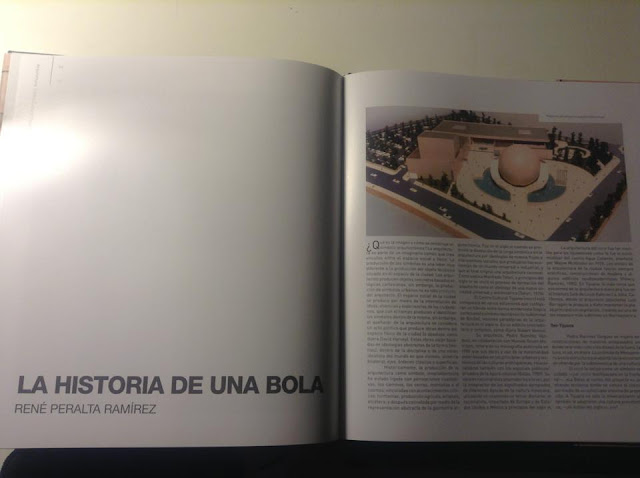

El Centro Cultural Tijuana (Cecut) está compuesto de varios volúmenes que configuran un híbrido entre forma modernista (lógica cartesiana) y símbolo neoclásico (lo subliminal de Boulle), visiones paradójicas de la arquitectura en el siglo xx. Es un edificio contradictorio y complejo, como dijera Robert Venturi.

Su arquitecto, Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, en colaboración con Manuel Rosen Morrison, reitera en su monografía publicada en 1989 que sus obras y uso de la materialidad están basadas en los principios urbanos y tectónicos de las culturas prehispánicas, relacionándose también con los espacios públicos/privados de la época colonial.[2]Su obra es nacionalista y posmoderna a la vez, por la integración de los significados apropiados de diferentes épocas de la cultura mexicana, utilizando en ocasiones un tercer discurso, el racionalista, importado de Europa y de Estados Unidos a México a principios del siglo xx.

La arquitectura del Cecut fue tan insólita para los tijuanenses como lo fue el estilo mudéjar del casino Agua Caliente, diseñado por Wayne McAllister en 1928. Los estilos de la arquitectura de la ciudad fueron siempre eclécticos, construcciones de madera y algunos edificios seudomodernistas.[3]En Tijuana, lo más cerca que estuvimos de la arquitectura mexicana fue en el Instituto Salk de Louis Kahn en La Jolla, California, donde el arquitecto jalisciense Luis Barragán le propuso a Kahn mantener la plaza principal sin vegetación, creando así uno de los espacios más sublimes en Norteamérica.

Teo-Tijuana

Pedro Ramírez Vázquez se inspiró en construcciones de nuestros antepasados en donde se brinda culto a los dioses de la lluvia, la luna, el sol, etcétera. La pirámide de Mesoamérica es la estructura que apunta hacia el cosmos en ofrenda por la sobrevivencia de una cultura.

El Cecut lo utiliza como un símbolo reciclado ‒¡un remix teotihuacano en la frontera!‒. “La Bola” al centro del proyecto es una ofrenda tectónica donde se simula el cosmos por medio de un sofisticado sistema de proyección. A Tijuana no sólo la mexicanizaron sino también le adaptaron una cultura precolombina, ‒¡el Aztlán del siglo xx, ese!

El Centro Cultural y Turístico de Tijuana (su razón social) fue el toque final de una propuesta nacional para la recomposición urbana de la ciudad. El proyecto urbano impulsado por el gobierno federal y trazado por el arquitecto Pedro Moctezuma fue el intento por mexicanizar Tijuana, ya que por ubicación geográfica y desde su concepción Tijuana sufría de una falta de mexicanidad, como bien lo resaltó el escritor Raymond Chandler en su novela The Last Goodbye: “Tijuana is not Mexico”.

Actualmente vemos que la traza urbana de lo que hoy conocemos como la Zona del Río fue un eje importante para la colocación de héroes nacionales en glorietas semejantes a las del Paseo de la Reforma en la capital de país. Tijuana por fin reconoció su mexicanidad. Junto con el canal de concreto más grande construido en el país, Tijuana ahora lucía lista para su modernización, su imagen era impulsada por visiones centralistas y una arquitectura de Estado, como explica el investigador Tito Alegría:

La virtud de Ramírez Vázquez consiste en haber reutilizado formas y principios surgidos en las batallas anti-historicistas, amalgamados con conceptos de origen prehispánicos, para darle a la arquitectura del poder el consenso necesario para que la gente sienta solucionada su necesidad expresiva y el Estado ejecute presencia en el territorio a través de la arquitectura, es decir, una finalidad aún histórica.[4]

La Bola cosmo-política

Revestido en concreto y organizado en simples volúmenes, ¡el Cecut pesa! Su materialidad se impone sobre la historia arquitectónica de la ciudad, después del casino Agua Caliente, es una de las inversiones más importantes que se han dado en la ciudad.

El museo y la sala de espectáculos configuran una “l”, que forma una plaza donde se ubica La Bola, que funge como sala de proyección omnimax en forma esférica. La Bola, como la bautizaron los ciudadanos, muchas veces se ha relacionado con la obra de Étienne-Louis Boullée y su proyecto para el Cenotafio a Newton. Comparativamente con la obra de Boulle, el omnimaxproyecta el cosmos sin representar los ideales neoclásicos del arquitecto francés (lo sublime), La Bola, en tanto, tiene más parecido a una obra de Béton brut, parte del movimiento arquitectónico que decribió el crítico inglés Rayner Banham como brutalista. La Bolahace referencia a su funcionalidad y en conjunto es ubicada al centro de la plaza limitando la congregación interrumpida de los usuarios como en los zócalos tradicionales, La Bola es, pues, el elemento ordenador del Cecut, todo lo demás es un intersticio.

Las caras de la Bola

El Cecut se ha convertido en la plataforma artística local, representado la contrariedad entre lo nacional y lo fronterizo, donde las visiones de una realidad urbana y una imagen nacional han discutido su convivencia. En 1994 el artista tijuanense Marcos Ramírez erre participó en el evento artístico binacional InSite, con la obra de instalación titulada Century 21, consistente en una casa construida con material reciclado y residuos provenientes de Estados Unidos, como las miles de viviendas que se encuentran en la periferia de la ciudad; viviendas para trabajadores de maquilas que ganan sólo lo suficiente para construir una casa de madera. La obra de erre se contrapone a la visión centralista (externa) e institucional con la realidad de los procesos de crecimiento informal de la ciudad y de la memoria del forzoso desalojo de Cartolandia, favela instalada sobre el Río Tijuana antes de su canalización. En el catálogo más reciente del artista se describe la obra de esta forma:

La instalación fue colocada en la explanada principal de Centro Cultural Tijuana (Cecut) creando una yuxtaposición entre la monumentalidad y solidez de la arquitectura institucional mexicana y la fragilidad entre una estructura nómada, simbólica de un insurgente y flexible urbanismo.[5]

No sólo los artistas locales, sino también los extranjeros han utilizado al Cecut como referente de la contradicción representada por la imagen urbana de Tijuana, una realidad inevitable de reconocer. En otra edición de InSite, en el año 2000, el artista polaco Krzysztof Wodisczko proyectó sobre La Bola imágenes de los rostros de mujeres trabajadoras de la industria maquiladora que narraban en vivo su testimonio sobre su condición familiar, abusos laborales, entre otras realidades que viven cientos de trabajadoras que ensamblan todo tipo de productos para el mundo; por una noche La Bola obtuvo rostro pero no fue el de un diosa mexica o de algún revolucionario, sino el de los ciudadanos que viven en la periferias pobres de Tijuana, más alejados geográficamente del Cecut.

¿Dónde quedó La Bola?

Desde su fundación hace treinta años, el Cecut ha estado trasformando su significado, primero se construyó como un bastión de la mexicanidad, después lo adoptaron como lugar donde la cultura fronteriza legitima sus procesos locales por medio de confrontaciones con la curaduría y con el edificio mismo. Finalmente, intenta por medio de un cambio arquitectónico ‒con la construcción de El Cubo y la cineteca Sala “Carlos Monsiváis”‒ construir un nuevo diálogo con la cultura local.

Para el ciudadano común todavía es una incógnita lo que pasa o puede pasar en el Cecut. Una encuesta llevada a cabo en 2012 por un semanario local (una muestra de 400 entrevistas), indica que 45.5% de los ciudadanos encuestados no visitan el CECUT porque no les llama la atención y sólo el 47.5% supo que había dentro de “la Bola”.(7) La incógnita de los tijuanenses es un sentimiento común en la crisis de la institución del museo a nivel global. El efecto Bilbao de la década de los años 90 intentó presentar la arquitectura del museo como parte de la rehabilitación urbana de la ciudad post-industrial. En muchas otras ciudades del mundo se inicia una confianza en la imagen de la arquitectura estelar, ya sean museos, estadios o bibliotecas, produciendo en muchas ocasiones la incongruencia del deseo de la construcción de la modernidad por encima de tejido urbano social desprotegido.

La función de los museos del México moderno era conservar y recontextualizar el patrimonio histórico a través de una política de Estado, como menciona el sociólogo Néstor García Canclini: “Los museos en México tuvieron la tarea de proponer una monumentalización y ritualización nacional de la cultura”.[6]El Cecut se encuentra en tiempo de transformarse en una institución abierta que promueva la cultura local, que de alguna forma ya es parte de la actividad nacional, aquí en Tijuana se han formado no sólo artistas sino también promotores culturales que han llevado su conocimiento a otras partes del país y de América Latina. El edificio tiene sus límites, su espacio absoluto; su desarrollo debe ser tecnológico y ubicuo, nuestras instituciones tendrán que descentralizarse y dejar de ser sólo el lugar de la élite ‒el lugar para ser visto como en la gran escalera de la ópera de Garnier‒ y extenderse por la ciudad de forma virtual creando un fuerte lazo entre las comunidades que le falta por convencer.

Fuentes

Alegría, Tito, “El Centro Cultural Tijuana: Crítica de arquitectura”, Esquina Baja, Tijuana, México, Asociación Cultural Río Rita, núm. 2, 1987.

Galas, Miguel, Ramírez Vázquez, México, García Valadez Editores, 1989.

García Canclini, Néstor, Hybrid Cultures: Strategies for Entering and Leaving Modernity, Minneapolis, mn, E.U.A., University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Piñera Ramírez, David, Historia de Tijuana. Semblanza general, Tijuana, México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, 1985.

Sanromán, Lucía, y César García, Marcos Ramírez erre, México, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2011.

Sánchez, Osvaldo (ed.), Fugitive Sites: InSite 2000-2001, San Diego, ca, E.U.A., Installation Gallery, 2002.

Tafuri, Manfredo, Architecture and Utopia, Boston, mit Press, 1976.

[1] Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia, Boston, mit Press, 1976.

[2] Miguel Galas, Ramírez Vázquez, México, García Valadez Editores, 1989.

[3] David Piñera Ramírez, Historia de Tijuana. Semblanza general, Tijuana, México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, 1985.

[4] Tito Alegría, “El Centro Cultural Tijuana: Crítica de arquitectura”, Esquina Baja, Tijuana, México, Asociación Cultural Río Rita, núm. 2, 1987.

[5] Lucia Sanromán y César García, Marcos Ramírez erre, México, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2011.

[6] Néstor García Canclini, Hybrid Cultures: Strategies for Entering and Leaving Modernity, Minneapolis, mn, E.U.A., University of Minnesota Press, 2001.