mini articulo sobre los conceptos contextuales que preocupan a generica . generica es la oficina de arquitectura que inicie en 2000 con la intencion de crear una practica alternativa de la arquitectura por medio de proyectos e investigacion. este texto – es un borrador -para el catalogo de la bienal de california 2008 organizado por el orange county museum of art y Lauri Firstenberg, directora de LAX Art en Los angeles.

Tijuana’s haunt

“In Tijuana everybody seems to be a poet or a painter.”

Anthem magazine, 2004

At the end of the 20th century economic and socio-political dynamics have encouraged the creation of countless “alternative” artistic praxis within the city of Tijuana. Artists have been involved in the reflection of contemporary issues pertaining to the volatile life of the US/Mexico border. The most considerable experimentation with alternative versions of art practice has taken place in the realms of literature and visual arts. A search for an understanding of border identity has produced conceptual versions of the city from writers and academics alike, that span counter culture narratives to post modern theory. The challenges that the region presents form part of a necessity to reach a general or open definition of “border” urban and social space. Nestor Garcia Canclini became an important influence in the re-reading (or impossibility of a congruent reading) of social and urban space produced by an incongruent visual urban system created by cultural hybridity of constructions and their users. In his text Hybrid Cultures, hybridity is an important concept through which we can understand the process that composes the social and spatial conditions of the border city. In the space of the contemporary city, the lack of urban regulation and the hybrid culture of architectures form a mismatch of styles, together with the interaction of monuments and advertisement, situates in heteroclite networks the visual order and memory of the city. Canclini explains tensions of de- territorialization and re-territorialization; the loss of innate relationships between culture, geography and social territories and at the same time territorial relocations of new and old symbolic productions (Canclini, 1990).

Tijuana then is an example of this great hybrid experiment where the notion of authentic culture and identity is no longer credible within its urban form, the city mixes desires and symbols that have a relation with a simulated history of the city itself. Tijuana defines its identity as a simulation that requires the production of hybrid readings. Its geographical location and abstract codes has put in place the symbols and mechanisms for an art to emerge. Heriberto Yepez, a young writer and philosophy professor from Tijuana has his doubts and remarks that Tijuana has not been defined by hybridity, but more importantly, since its origins has made a parody of the simulated hybridism (i.e. the donkey painted to resemble a zebra = zonkey) taking place in the border region. For Yepez, the concept of hybrid culture is a neo-liberal trap, a hegemonic discourse that intends to erase differences and realities of the border. In his book Made in Tijuana, Yepez continues his disarmament of the hybrid stating that it fundamental basis lies on a Hegelian synthesis that intends to fixate and surpass the same identities that produce the mix. The hybrid culture concept is no more than a metaphor, while the realities of the border are asymmetrical and in constant tension. The border region for Yepez is defined by economic and cultural disparity, fission of cultures rather that the consolidating concept of fusion that has been an ally of the hybrid discourse. “To understand the border we must de-hegelize ourselves”. (Yepez, 2005)

In both cases Canclini and Yepez endorse important artistic practices that somehow have included the discourse of identity and culture of the US/Mexico border. Some of these practices have promoted the fusion of language, cultural traditions, cross-cultural identity and other urban representations of post modernity as in the case of Guillermo Gomez Peña. While in Tijuana the artists Marcos Ramirez “Erre” and Jaime Ruiz Otis have formed practices dealing with conflict and respond to the disparities and tensions in the realm of culture, labor and bi-national politics.

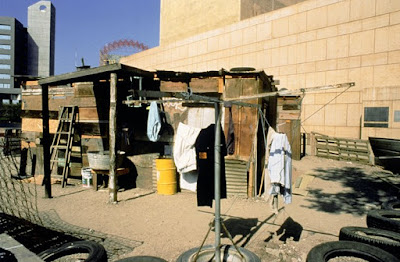

Century 21, created by Marco Ramirez “Erre” in 1994, is a project that has been important and popular concerning current conceptualizations of the border region and current phenomena of immigration, impact of globalization and other factors that have been critical to the development of the Tijuana/San Diego urban binomial The artist recreated a dwelling typical to the ones built in the informal settlements of the city on the esplanade of the Tijuana Cultural Center, designed in the late 70’s by the renown Mexican architects Pedro Ramirez Vazquez and Manuel Rosen Morrison, a building that represents the institutional modernism of the PRI party that ruled Mexico for more then 70 years. Century 21 intended to de-contextualize both structures by making apparent and visible the formal and tempo-spatial tension inherent in the large context of the city and realizing that the concept of border is illustrative of the inherent antagonism that haunts not only the US/Mexico region but is prevalent within the local urban space of the city of Tijuana. This tectonic confrontation found in Century 21 is analogous to the many paradoxical effects within the city and in the architectures of dyslexia that never intend to integrate into a synthesized form or space (hybrid), but engage in a violent dialogue temporarily resolved through a series of negotiating acts that are necessary for survival and coexistence.

Century 21 foto: insite 94/Marcos Ramirez -erre

The work of Erre brings to the forefront interesting issues and questions for architectural/urban practices to consider. Can we consider an urban model for the hybrid/fission counterparts? If these two primordial elements of the conceptualization of the border region and the city of Tijuana are trajectories of contemporary city life, can they produce spatial environments that are not only theoretical, but also physical and reproducible? There has been much intent to reproduce specific urban developments such as squatter city organizations and tectonic assemblies of informal constructions built by recycling construction material and other non-traditional building materials. Yet, somehow these intents have not been based on a profound study of the economic and social tensions that form and produce these urban settlements. In the past decade we have witnessed mere simulations and creation of a myth of a system that is inherently filled with plurality and spatial heterogeneity and that it seems to mythically work and become prescriptive once it is de-contextualized – an exemplary post modern idea. The issues of hybridity and other conceptualizations of the border are part of a political discourse, yet difficult to interpret as prescriptive urban organizations or architectonic assemblages. As Nezar AlSayyad mentions,

The assumption that hybrid environments simply accommodate or encourage pluralistic tendencies or multicultural practices should be turned on its head. Hybrid people do not always create hybrid places and hybrid places do not always accommodate hybrid people. All that can be hoped for at the beginning of the 21st century are environments that harbor the potential for growth and change and peoples who may find the possibility of adapting and adopting otherness as a legitimate form of self-identification. (AlSayyad, 2001)

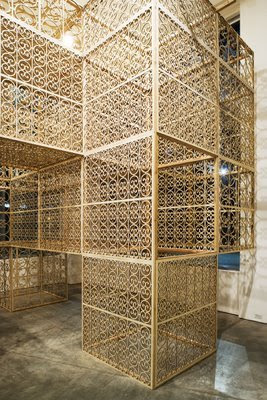

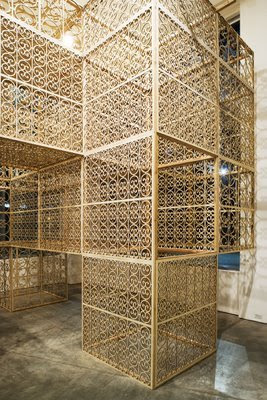

In the last 8 years the Tijuana based architectural firm of Generica has been experimenting with a sort of bottom up theoretical field where the practice expands and contracts as it absorbs urban implications. Located in the border, the mechanism of critical practice such as the access to new forms of technology (be it material, computational or academic) are not always available or economically feasible. What is at hand is the social and cultural dynamics of the border and its urban space. Generica, as a practice tries to integrate methods of analysis that can therefore react specifically to a varied realm of conceptual and real circumstances. In many cases the process of production includes many non architectural techniques such as film, multidisciplinary research, site specific installation and writing. It is between these alternate and/or alternative mediums that the firm integrates conceptual dialogues, such as the ones already discussed, with the intent to identify the concepts that best describe the urban situation of the Tijuana/San Diego urban border. In a project entitled Contain(mex)3=Contiene(mex)3 Generica tapped into two sources of production; one industrial and the other conceptual. The installation was part of the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art exhibition Strange New World Art and Design from Tijuana and was constructed of laser cut wood modular panels designed with the familiar curl of residential security window and door metal screens. The objective was to use the technological apparatus found in the manufacturing industry of the free trade border zone and employ a facility with a digital laser cutter used for producing mechanical parts for the different assembly plants across the border. A direct implementation of skills and technology reserved for foreign industries taking advantage of cheap labor. The pattern laser cut on the panels was derived from a study of the urban proliferation of security screens in residential and commercial constructions throughout the city. A symbol of fear as well as an aesthetic element that has now become a standard architectural feature recognizable by all. The final configuration of the piece did not intended to mimic and de-contextualized a house inside the San Diego Museum emulating Erres Century 21, but became a cube whose configuration adapted to the visual, atmospheric and spatial constraints of the gallery. The result was not blatantly political, but intended to reconstruct, at least in a phenomenological sense, the space of border threshold.

Contain(mex)3=Contiene(mex)3 foto: Pablo Mason/MCASD

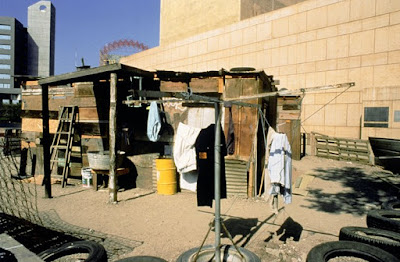

The concept of hybridty has become an important discussion in the history of postmodern border art. Artist have intended to discuss issues of identity and multiculturalism though ideas in favor or against it and recently writers like Heriberto Yepez have critically engaged the tactics of border art and their urgent dilemmas within the realm of asymmetrical globalization of the border. In regards to urban and architectural practice I would like to think they exist or they might be mere fantasy in a city of myths. Tijuana is a city where 50% of all residential construction in the city is of illicit origin and self constructed (Alegria 2005). In the last twenty years the east side of Tijuana has grown beyond its critical mass, housing conditions have moved from being self built favelas to a phenomena of overnight density – drag and drop suburbs are becoming the normative housing strategy for the working class. What is fascinating is the determination of the population to appropriate urbanism and model it through their own idiosyncrasies.

Villa Fontana, Tijuana. foto: Rene Peralta

Villa Fontana, Tijuana. foto: Rene Peralta

Architects have had a passive role in the construction of the urban realm. Major urban developments have been made through forceful intervention, foreign and national; in the name of de-codifying the Mexican border with a national modern style or as a place of architectonic de-contextualization such as the Agua Caliente Casino designed in a Moorish/Mission Revival style for the mob by a San Diego teenage draftsman named Wayne McAllister in 1928 (Nichols 2007). Since its conception, this city that border created, has had episodes of urban consolidation as well as instances of rampant and irregular development. Art practices have evolved much efficiently within the codes and concepts that intent to define the urban border. It seems that urban spatial practices still need to mature into elaborate multifunctional networks that can find resources and mechanism for a sense of criticality and adaptation. It might be that in Tijuana everybody is [only] a poet or a painter, at least for now.

Rene Peralta

Works cited:

AlSayyad, Nezar. Hyrbid Urbanism Praeger Publisher. 2001

Alegria, Tito. Legalizando La Ciudad Asentamientos Informales y Procesos de Regularización en Tijuana. El Colegio de La Frontera Norte, 2005.

Canclini, Nestor Garcia. Culturas Hibridas. Grijalbo. 1990.

Montezemolo,F Peralta,R Yepez,H. Here is Tijuana. Black Dog. London. 2006.

Nichols, Chris. The Leisure Architecture of Wayne McAllister. Gibbs Smith. Utah. 2007.

Yepez, Heriberto. Made in Tijuana. ICBC. Mexico. 2005.