Desarticulando la Memoria – El Toreo de Tijuana 1957 – 2007

1. There is no architecture without action, no architecture without events, no architecture without program

2. By extension, there is no architecture without violence.

Bernard Tschumi, Architecture and Disjunction, MIT,Press. 1984

¿Por que se condena al Toreo de Tijuana a la pena de muerte, acaso será por su vejez? ¿Acaso es un crimen vivir más de 70 años como artefacto histórico de la ciudad? Según las autoridades, la estructura ya cumplió su función y por eso tendrá que ser desmantelado, dejando a la ciudadanía aceptar que la única función de un edificio es su estabilidad estructural y no la relación histórica urbana que se creó con el tiempo entre ciudad e inmueble. Y si su función estructural es obsoleta (que en gran parte lo dudo por su construcción de acero) no habría quienes (Colegio de Arquitectos e Ingenieros) pudiesen hacer una revisión y adaptación de la estructura para su rehabilitación.

Bertrand Lemoine, Eiffel ,Stylos, España 1986

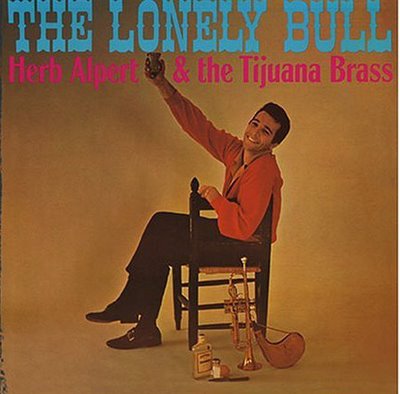

Alpert set up a small recording studio in his garage and was overdubbing a tune called “Twinkle Star” when, during a visit to Tijuana, Mexico, he happened to hear a mariachi band while attending a bullfight. Following the experience, Alpert recalled that he was “inspired to find a way to musically express what [he] felt while watching the wild responses of the crowd, and hearing the brass musicians introducing each new event with rousing fanfare.” Alpert adapted the trumpet style to the tune, mixed in crowd cheers and other noises to create ambiance, and renamed the song, “The Lonely Bull.” He paid out of his own pocket to press the record as a single, and it spread through radio DJs until it caught on and became a Top Ten hit in 1963. He followed up quickly with an album of “The Lonely Bull” and other titles.

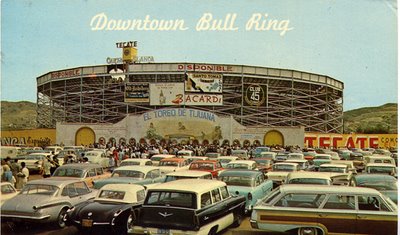

El toreo fue parte del trío turístico (hipódromo, toreo, jailai) que en la segunda década del siglo XX representaba la oferta cultural de la ciudad. Tijuana representada por el juego y el espectáculo de hombre contra bestia, bestia contra bestia y hombre contra hombre. Su fachada es singular en el sentido de que no existe, la estructura se penetra para poder entrar – el toreo es un interior al aire libre. Su forma circular es la más próxima semejanza a la real urbis romana, política-espacial. Aparte de la nostalgia que me produce la destrucción del toreo, me cuestiono su razón y, quizás ya muy tarde, quiero entender cuál es la relación semiótica con la sociedad y que labor jugó en la socialización de la misma. Al final no me queda mas que reflexionar sobre estas dudas y mantenerme atento de que no le pase lo mismo al Jai Alai.