Posts para el blog de Insite: www.insite05.org

Blog/ Border Crossing 1: Memoria, imagen, historia y ciudad.

Nov.02

El espacio publico ya desapareció, como dice baudrillard “The body as a stage, the landscape as a stage and time as a stage are slowly disappearing. The same holds true for the public space: the theater of the social and of the politics are progressively being reduced to a shapeless, multiheaded body. En cuanto a leerla se me hace difícil entender a la ciudad contemporánea como lectura, ciudades que no existen dentro del espacio perspectivista por que no se ubican puntos de referencia convirtiéndose en una lectura que quizás todavía no sabemos leer.

Nov. 03

Ciudades sin referencias, ciudades sin centro como lo explica Heriberto Yépez. En el centro también menciona Barthes existe la verdad. Los valores de la civilización se encuentran en el centro – ir al centro es estar dentro del espacio de la verdad social. Pero Tijuana no tiene centro, es similar a la crítica que hace Deleuze al cine de Godard cuando lo llama abstracto.

Pero no se refiere a una ausencia de narrativa sino a una yuxtaposición de elementos que crean una continuidad no-narrable. (Rajchman). Esta continuidad abstracta creada por una condición de la “urban singularity” tomando el concepto de Vernon Vinge, en un tiempo futuro, cuando el cambio social, científico y económico sean tan acelerados que no podremos imaginarlo desde nuestra perspectiva del presente. Cuando la humanidad se convierte en post-humanidad. La post-urbanidad que vive Tijuana nos ocasiona una dislexia visual como dice Virilio, una sociedad incapaz de representar su ciudad a si misma.

Nov. 04

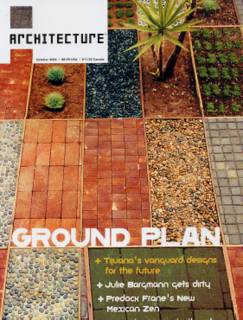

La imagen de Tijuana es ubicua, la vemos en cada rincón de la ciudad, una imagen formada por procesos. Tijuana no es una ciudad legítima, auténtica, al contrario fue formada por actos ilícitos y violentos. Desde sus inicios en la guerra México- Americana donde se convierte en el límite territorial de México a la mayor parte de las etapas de desarrollo infectadas de procesos violentos (invasiones, desalojos, filibusteros, narco, abusos, procesos actuales de preinscripción de tierras que se señalan como legales). Tijuana siempre ha tenido una confrontación con su geografía -una imagen de hostilidad entre lo natural y la necesidad.

La imagen de San Diego se relaciona con la naturaleza – una imagen rural.

El aislamiento de sus comunidades crea lugares simulados (algunos hasta con lagos artificiales) el concepto de suburbio “sprawl” esta siendo adoptado por el mismo centro urbano “downtown”cambiando la fisonomía actual hacia una homogeneidad.

Unas de las propuestas más importantes para el futuro desarrollo de San Diego lo elaboraron Donald Appleyard y Kevin Lynch en los 70’s llamándolo Temporary Paradise – una simbiosis con su entorno natural. Es obvia la influencia de un paisajismo como proyecto urbano simulando la ciudad orgánica de Mumford o Broadacres de Frank Lloyd Wright. Un edén, el paraíso terrenal, pero a la vez con una barda perimetral y un foso militar. Estos “setbacks” son militarizados – al Norte Camp Pendleton (campo de entrenamiento del ejército) al Sur el estuario y el bordo de metal (parte de un base naval y extensamente patrullado por el border patrol) y al Oeste la base de la flota naval mas importante del pacífico.

Las dos imágenes de ciudad son sumamente complejas para mí. En la novela de HG Wells “The Time Machine” el viajero se encuentra con un futuro divido entre dos mundos. Uno feliz donde los habitantes viven entre la naturaleza, sin guerra o ejércitos llenos de alegría pero con una vida sin sustento. El otro existe debajo del subsuelo en las tinieblas. En este mundo los habitantes trabajan de día y suben al edén de noche para aterrorizar a los frágiles y temerosos Eloi.

Menciono a Wells por ser una novela infantil y quizás más aceptada para este blog que otros textos teóricos ya mencionados, y también para marcar que las diferencias entre los de “arriba” y los de “abajo” crean una coexistencia hecha de fantasías y realidades.

Rene Peralta – Tijuana