Confronted with transnational concerns surrounding migration, globalization, economic instability, political turmoil, ecology, and social justice, this panel will discuss modes of engagement via critical spatial practices. The panel includes theorists and practitioners in architecture, urbanism, planning, and the social sciences that examine emerging conditions across Latin America, the US-Mexico Borderlands, and the broader Global South. Themes include informal settlements, tactical urbanism, migrant geographies, participatory practices, sustainability, and related topics. Which issues are reshaping cities across these regions? How do emerging urbanisms shift our expectations for design practice? Who are the stakeholders and how do they collaborate? Can critical spatial practices shape more inclusive metropolitan futures?

ACSA

EMERGING URBANISMS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE GLOBAL SOUTH

Presentation notes _Esperanza de Mexico

June 18, 2020

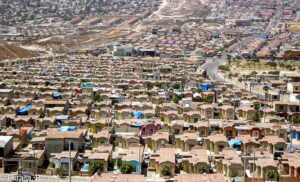

Since the 1960s The city of Tijuana and the major border cities on the Mexican northern border in general have experienced high levels of migration from all corners of Mexico as well from central and south America.

The national economic programs of Programa Nacional Fronterizo (1960-1965) and Programa de Industrialización Fronteriza (1965) drew many migrants to find work in the construction and manufacturing industry.

These programs set the stage for an open and binational economy at the border creating a different economic scenario from the rest of the country.

|

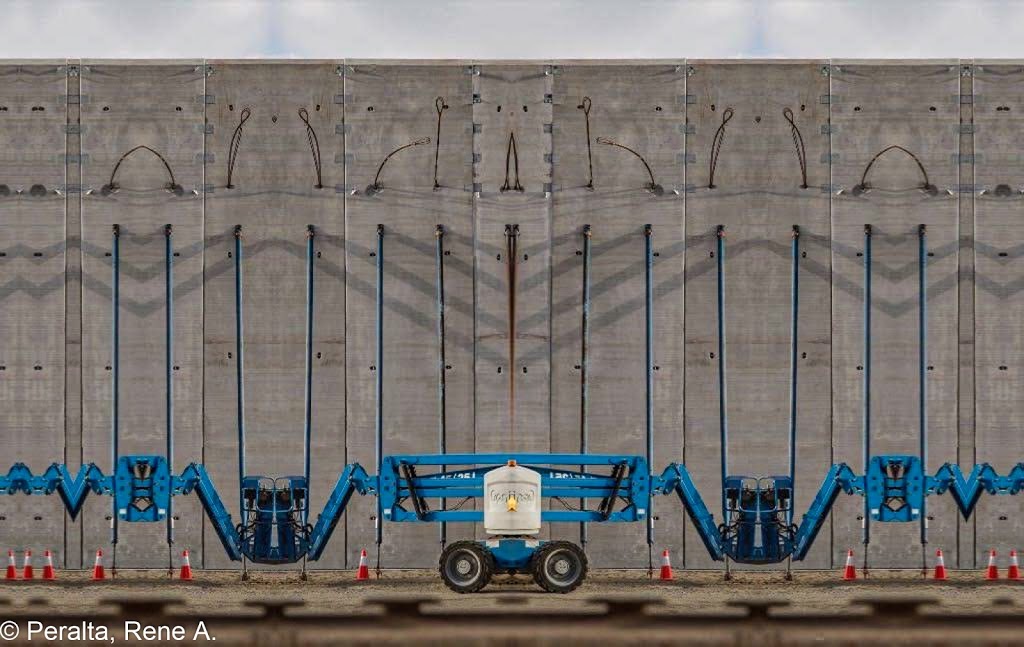

| Photo Rene Peralta |

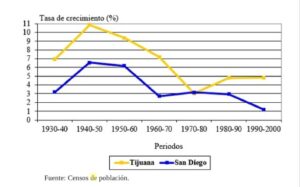

The rate of demographic growth until the 1970s was parallel with neighboring San Diego then they merged.

Soon Tijuana’s demographic growth increased due to the economic realities of a more globalized economy promoted by manufacturing the industry also known as the Maquiladora Industry.

As the city grew new communities were created along the periphery of the city.

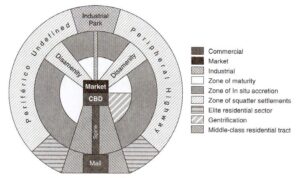

Tijuana in terms of urban planning is a typical Latin American city organized with central zones and radial sectors as described in the Griffin and Ford model.

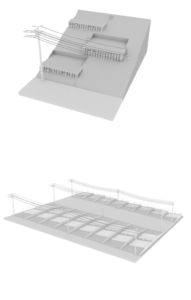

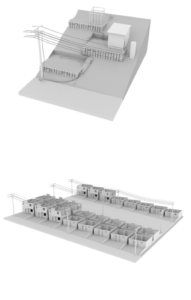

In Mexico, it is estimated that 70% of the population, self builds its own home with traditional materials such as concrete blocks or brick, and in some instances with second-hand timber from other construction sites or even other countries as is the case of cities along the US/Mex border.

|

| Photo: Rene Peralta |

Yet many of these houses lack construction supervision by a professional or government agency, they are fragile constructions that do not hold up well in harsh climates and lack well maintained electrical and plumbing systems.

Also, the only options provided to the working-class population had been the developer micro-sized units that did not abide by the size of a common Mexican family, creating segregated and overcrowded horizontal ghettos around the major cities in the country.

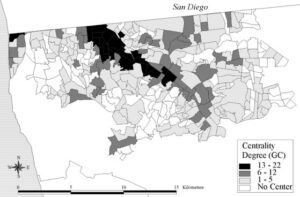

Maquila and centrality

|

| Photos: COLEF |

Maquiladoras are manufacturing plants that take advantage of cheap labor and relaxed environmental regulations that find the dumping of hazardous materials overlooked by the Mexican authorities.

The Maquiladoras promoted jobs and security to an incoming population that settled rapidly in the eastern part of the city, an informal process that began through property invasion.

|

| Photo: Ingrid Hernandez |

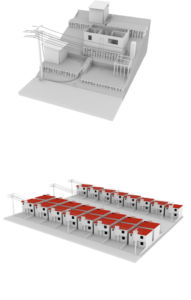

In comparison to these communities, the informal developments tend to improve with limited infrastructure as years pass and some have morphed into consolidated communities.

As the slow process of legalization and regularization, though public agencies made it possible for families to have property tenure, today their ability to build a dignified, permanent and structural sound home is still out of reach.

“…having a property title appears not to change the financial patterns of families very much. In Mexico among families whose income total less than six monthly minimum wages, only 10% made use of loans to invest in their homes”

(Alegria & Ordoñez, 2016).

From Informal to Formal and back.

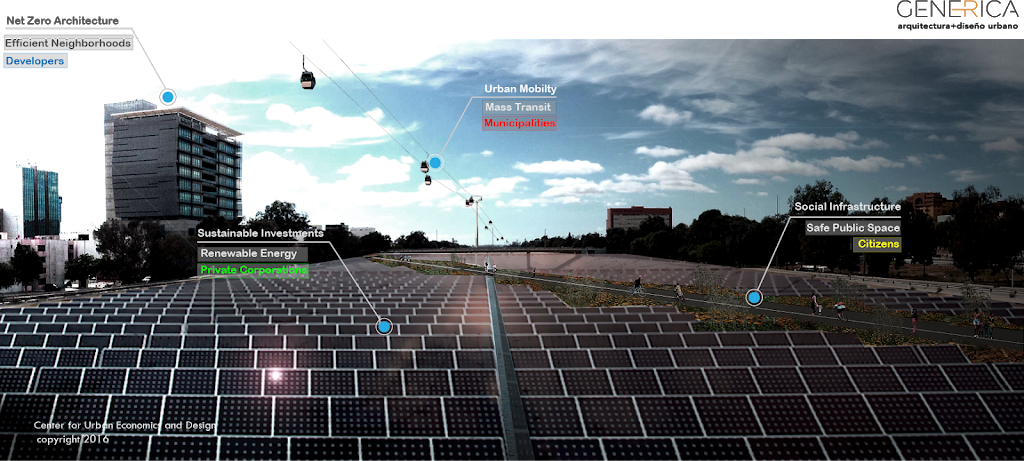

Diagrams: Rene Peralta