Infrastructure and European Integration: a review of a few essays from the Journal History and Technology Vol. 27, No. 3 September 2011.

I have always found the link between illustration graphics and manifestos, power, and political views fascinating. Many of the most critical projects that have shaped the ideas and concepts in architectural discourse have not been built. However, their representation (drawings, models, and texts) has been critical in producing new paradigms in architectural design.

Borders and Infrastructure

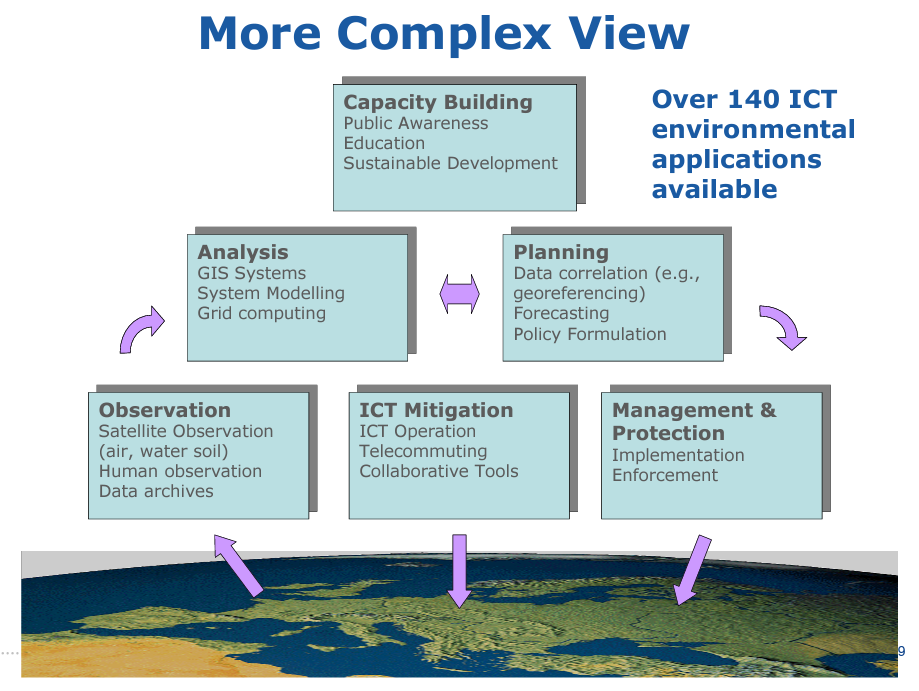

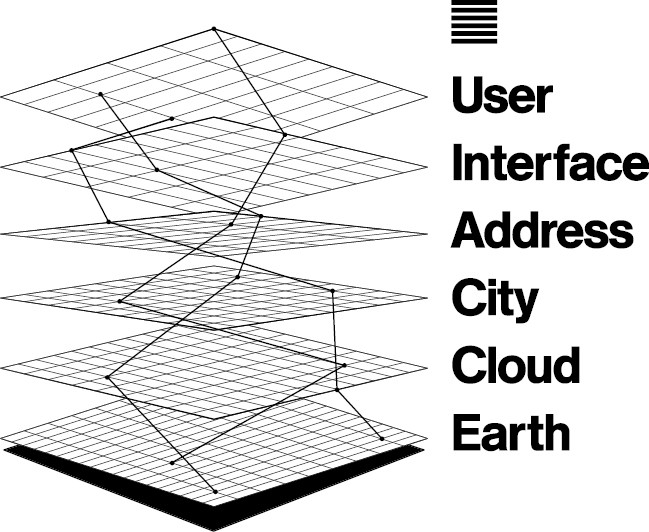

In the special issue of History and Technology devoted to Infrastructural Europeanism, Schipper and Schot point out the importance of infrastructure in nation and region integration in Europe. The first intent for continent integration was in 1950 with the Coal and Steel Community, an organization with power beyond borders. The authors identify these attempts to construct a new Europe by building and administrating infrastructures across national borders. This notion of infrastructural globalism was a “project for permanent unified, world-scale institutional, technological complexes that generate globalist information not merely by accident, a by-product of other goals but by design” (Schipper & Schot, 2011). Moreover, the term “infrastructure” had to be re-defined and accepted beyond the standard French definition. By 1950 the word was part of the semantic dispute. One of its most vocal critics was Winston Churchill, who said, “The original authorship is obscure, but it may well be that these words’ infra and ‘supra’ have been introduced into our current political parlance by the band of intellectual highbrows who are naturally anxious to impress British labour with the fact that they learned Latin at Winchester.”

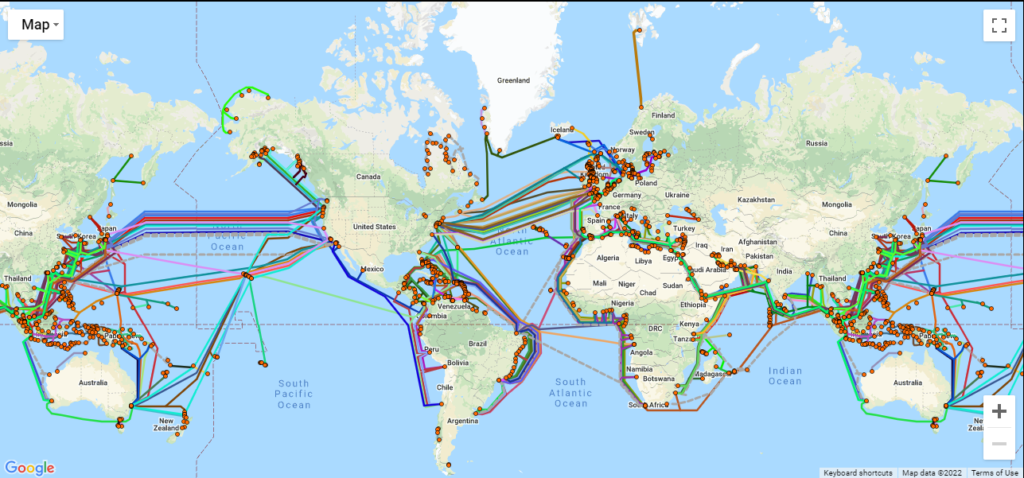

This rebuke did not prevail, and by 1960 the term referred to other non-material networks such as social and communication infrastructures. Historians explain that infrastructure created an imagined European community of transnational networks. It is relevant to point out that the emphasis on infrastructure making went beyond national or regional boundaries. It also dealt with global issues such as cross-border flows of people, goods, data, and energy. By 1990, Europe was a ‘zero-friction society’ with seamless mobility of capital, goods, people, and services. Today, this European seamless mobility is still limited to certain countries and excludes others, as in the case of some eastern European nations (Schipper & Schot, 2011).

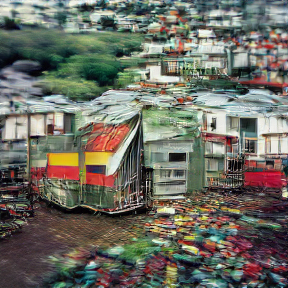

The US/MX border region may have something to learn from the integration efforts of mid-twentieth-century Europe. Yet, there is a history of racism and xenophobia is still much alive in the territory. Across the American border region, some challenges might be resolved by shared or mutually conceived infrastructures. However, a difference from the European example is that the US/MX border region is a contested political space. More than an imaginary border or region (Anderson), it is a ‘real’ place with border actors (citizens, commerce, industry, etc.) and institutions creating binational policies. The border is a physical place and usually consists of cities from both countries coming together at the political division.

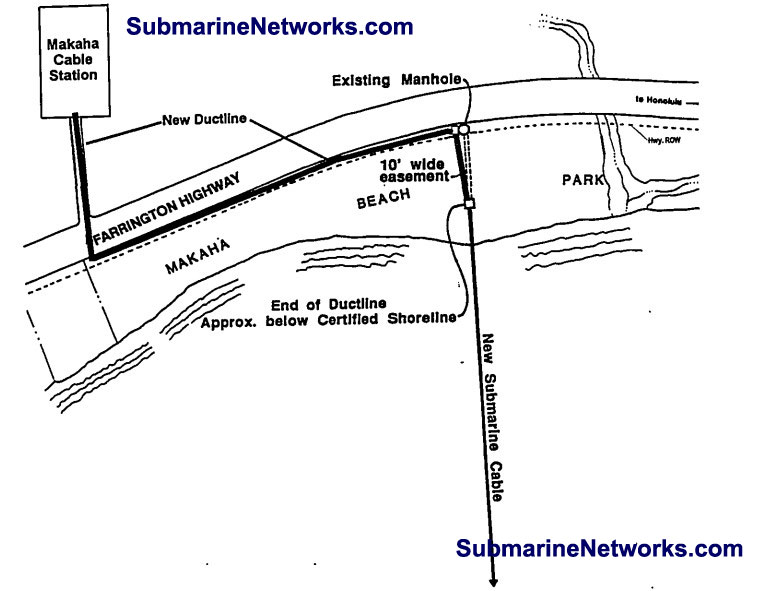

The lesson or questions are how a region of flows (people and goods) takes advantage of shared infrastructure, allowing regional sovereignty beyond the centralized visions of national capitals. The US/MX border cities are assemblages that can produce infrastructures capable of organizing social and technological infrastructure across borders.

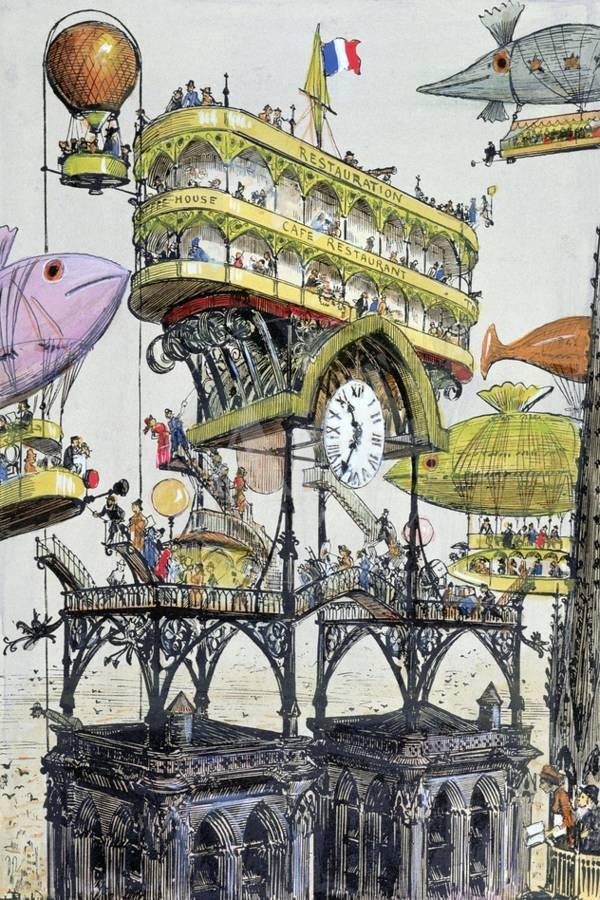

Image, Technology, and History

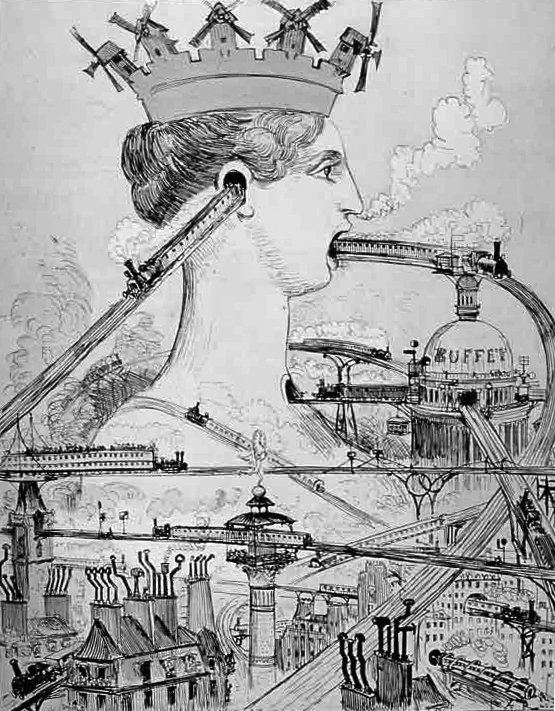

Images are a type of infrastructure; they communicate ideas, concepts, or the process of producing a design. They are powerful storytelling devices. Peter Soppelsa examines the cartoon or illustration of the Paris Metro by the French steampunk illustrator and science fiction novelist Albert Robida, published in 1886, portraying how the metro (railway system) might deform and violate the city “the queen city.” The author states, “It was a visual response to a visual problem” (Soppelsa, 2011). In opposition to the Haussmann metro project, a civil counter group was formed and led by Charles Garnier, a neoclassical architect known for designing the Paris Opera House. As a Neo classist Garnier looked at the past for inspiration and aesthetics, he produced significant buildings in Roman and Greek architecture. This form was fitting for elite buildings, signature pieces in the city. Therefore, his disdain for the metro was natural. He perceived structures and forms of steel as solely engineering. Infrastructure in a traditional sense must be invisible, undisruptive to the classical aesthetics of the city. In 1887, Garnier and a group of intellectuals launched an objection against the building of the Eiffel Tower, today a national symbol of France.

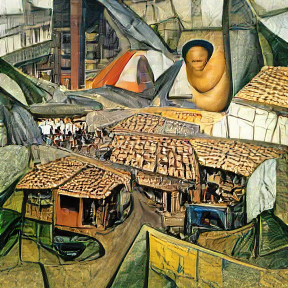

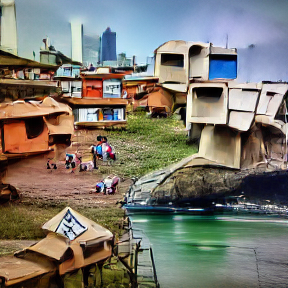

Very few cities today have a grand narrative. Infrastructure has been a driver of urban development, sustaining future growth based on demand, migration, labor dynamics, etc. The aesthetic of the postmodern city is one of collage and hybrid themes; there is no urban manifesto or Haussmanian hand that decides the future development or aesthetic of a city.

Images and concepts play an essential role in the marketing and politics of a city. Most cities have postcards with slogans and skylines that promote their economic attributes and urban lifestyles. Today, computer-generated images and models have become essential decision-making tools for government and communities. Through images, the public and policymakers can scrutinize a project (building or infrastructure) and its effect on a community by understanding its form, environmental impact, visual impression, and many other aesthetic and technical factors.

In the past decade, transportation infrastructure has been one of the major themes in urban development and resiliency projects. Along with urban strategies to safeguard and adapt to climate change, urban transportation, air travel, and personal mobility are now essential to planning projects that include housing, economic development, and public space. Max Hirsh evidences that images of infrastructure and technology are vital PR material for the developers and investors for project success and public acceptance (Hirsh, 2011). However, images of new and developing infrastructures tend to leave out the impact and variances that could occur as the general public appropriates these technologies. Within advertising images of services and goods, a particular user has a specific style of living or a suggested allure of transforming the user’s persona by its attainment. This is a common theme in the PR images of private developer condominiums towers in every major city. Buildings that search a specific market or try to create an appeal for a certain kind of living, most of the time the images are directed to upper-class citizens or private investors. This type of image advertising often steers a community into gentrification.

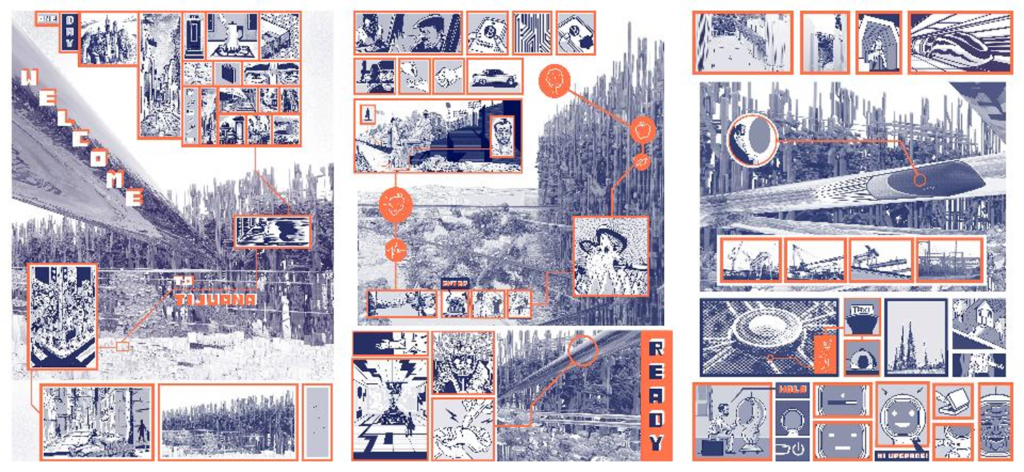

Max Hirsh concludes the text with two arguments. First, the typical user is absent from the official images and needs to be explicitly reintroduced. Therefore, instead of pictures of finished projects, a visual narrative based on a storyboard or comic strip can be helpful in the integration and understanding of infrastructure’s impact upon the broader public.

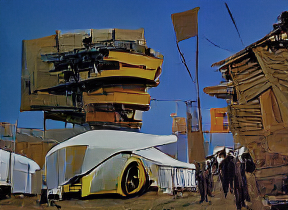

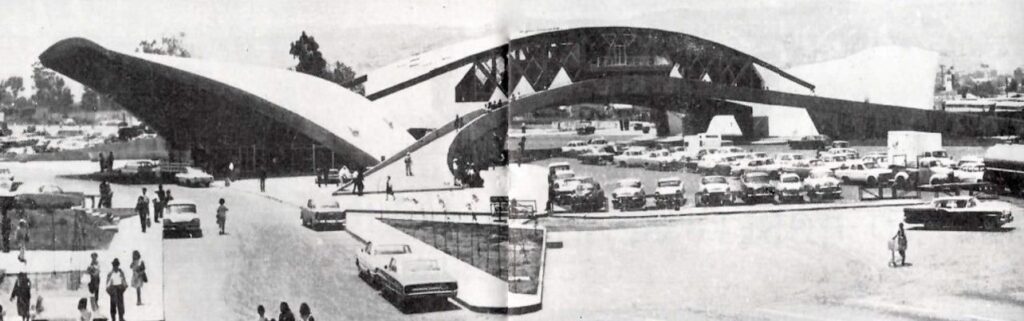

HyperloopMexa

In 2016 a team of colleagues and I developed a proposal for Hyperloop One, a cross-border system connecting Los Angeles, California, and Ensenada, Mexico. This technology uses a vacuum- tube system that would connect both cities in less than 20 minutes. An automobile journey takes approximately 4 hours, not including the wait at the international border. Currently, this technology is being developed by different private companies (Virgin Hyperloop, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, Hardt, among others), and all have invested in sophisticated PR images. Videos displaying how Hyperloop will change mobility and long-range transit in cities and regions where the system is implemented. However, the images presented display a system for a social class that is part of the business milieu who travel across regions and borders for business purposes. The pictures of the stations and transport pods are shown with the latest digital technology and stylized futuristic hygienic interiors. The future is always in white.

Our work in recent years has studied the realities of the places where the technology will operate, specifically in developing countries. As Max Hirsh points out, “Images provide scant information about how they operate in practice; or about how infrastructure systems, once built, are subsequently appropriated by their users and reconfigured to meet shifting political and economic demands” (Hirsh, 2011). Hyperloop technology images do not show or illustrate how the rest of the population will use and be affected by this disruptive transportation technology. We argued that workers in low-paying jobs such as in the hotel cleaning service, fast food service, landscaping, construction, among others, would be the frequent use of the system and not the Caucasian business class passengers that appear in the PR images. The narrative in the advertising for the system demonstrates a seamless integration between multimodal mobility infrastructure (tubes, stations, buses, etc.) within the urban fabric. However, we argue that as these technologies hit the ground, they will displace or be in conflict with traditional and stable private/public transport systems such as taxis, buses, and other modalities that operate organically in developing countries. New Technologies also discriminate against those who cannot pay for its service through images of social class hierarchies.

Works Cited

Hirsh, M. (2011). What’s missing from this picture? Using visual materials in Infrastructure studies. History and Technology, 379-387.

Schipper, F., & Schot, J. (2011). Infrastructural Europeanism. History and Technology, 245-264.

Soppelsa, P. (2011). Visualizing viaducts in 1880s Paris. History and Technology, 371-377.