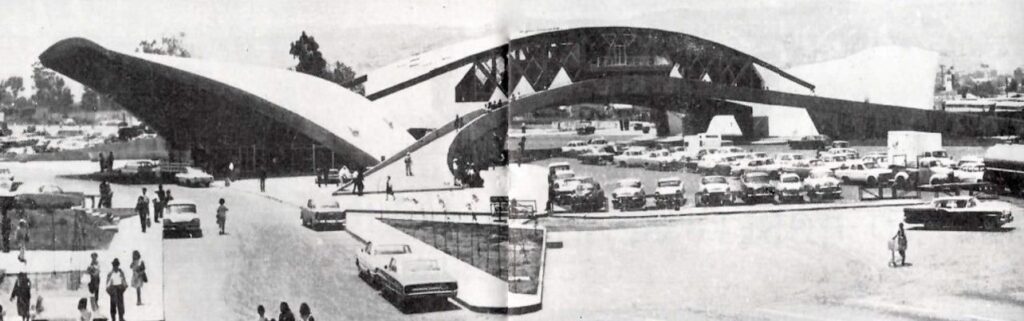

The hybrid structure, part bridge and part building flanked by two large paraboloids made of concrete housed the immigration offices of the Mexican government. It was colloquially known as “la concha” or the seashell to all who waited in line to cross into the US via the San Ysidro Port of Entry in Tijuana. The building was abandoned, uncared-for during its last years, and finally demolished in 2015. As Alejandra Lange points out, critics sometimes have to step into the role of activist (Lange, 2012), and when I found out that the federal government wanted to demolish the structure, I did. I joined others in the struggle to preserve the building. Historians, attorneys, artists, and the general public held live debates near the building to show solidarity for one of the last modernist buildings left in the city.

The building mattered because it complied with two of Riegl’s categories, use-value and newness value (Riegl, 1982). However, it was also a signature of Mexican modernism and paraboloid concrete construction made famous by Felix Candela. La Concha was a testament that there was a time when Mexico and Tijuana wanted to be modern. The building was not only a magnificent building but part of a more significant project, the modernization of ports of entry in Mexican border cities. Architect Mario Pani directed the federal initiative known as the Border National Project of 1965 and oversaw most of the design and construction for the country’s modern open land ports.

Lange, A. (2012). Writing About Architecture: Mastering the Language of Building and Cities. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Riegl, A. (1982). The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin. Oppositions 25, 21-51.