Category: Uncategorized

The Resilient Futures Symposium brings together experts from across the University of Oklahoma (OU) campus to share recent research and explore ways our environments may be adapted to facilitate well-being for both people and the planet.

The Resilient Futures Symposium is made possible with support from the OU Gibbs College of Architecture Bruce Goff Chair of Creative Architecture, as well as the OU Institute for Resilient Environmental and Energy Systems, OU Arts and Humanities Forum, OU Data Institute for Societal Challenges, OU Institute for Community and Society Transformation, and OU School of Visual Arts.

Changes in the earth’s climate necessitate a critical rethinking of how and where we live in order to imagine a more resilient and sustainable future for humans, plants, and animals. As severe weather intensifies, coastlines erode, forests burn, and water sources evaporate, millions of people are already being forced to migrate in search of habitable environments. Meanwhile, communities and economies must prepare for the devastating impacts of declining crop yields in the face of climate change. International conflicts are increasingly born out of the fight for diminishing resources resulting from the environmental impacts of climate change. Human migration, urbanization, and development are resulting in encroachment on animal habitats that have brought mankind into greater contact with animal species. The rise of inter-species contact precipitates a rise in the transmission of diseases across species most notably evident in the covid-19 pandemic. These events unfolding around the world have made clear that in addition to trying to slow climate change, we need to think about how to adapt to it. As Martin Pederson and Steven Bingler put it, “If Plan A was to prevent, or at least mitigate, the most serious impacts of climate change, what’s Plan B?” How can we imagine a more resilient future?

The dramatic effects of climate change demand a rethinking of how we inhabit the planet: where we live, how we utilize natural resources, and how we co-exist with other species. To date, however, much effort has been dedicated to mitigating the effects of climate change by reducing dependence on fossil fuels, developing more sustainable energy sources, rethinking manufacturing and waste cycles, and more. Despite these efforts, the facts are clear. The planet is warming. As the OU VPR Strategic Plan describes, “The Global Risks Report 2020 of the World Economic Forum identified extreme weather, climate action failure, natural disasters, biodiversity loss, and human- made environmental disasters as the top five global risks.” Alongside efforts to slow climate change, we must also turn our attention and energy to planning for how to best live with its inevitable effects. While mitigation efforts should continue; we must plan for a future defined by mass migrations of species. Where will we live next? Is it possible, for example, for climate refugees to re-occupy post-industrial cities or rural towns that have lost population? How do we support health and well-being amid such drastic change?

Watch Here

The state of AI web applications for architecture today. And what does the future hold for A.I. technology, architecture, and design?

Architecture is a profession that requires a very complex set of skills, and architecture students have to learn how to use many different types of software before they graduate. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning in the design industry has given architects access to new tools that can help them with their work.

The state of AI web applications for architecture today.

The world of architecture has always lagged behind the world of technology. That doesn’t mean that technology never impacted the architecture profession. Computers were around since the ‘70s, and computers in architecture offices were around since the ‘80s. But all these computer-powered architectural tools and A.I. software solutions (like Revit) came to fruition at least twenty years after such tools showed up in countless other professions, like medicine and engineering, for instance. Still, despite this very apparent lag, many potential synergies between architecture and A.I. have emerged lately, especially within computer vision and machine learning.

Artificial Intelligence (or A.I.) is a topic that often makes the headlines across many industries. Architecture and design will flood into multiple facets of our lives. Whether you believe it or not, artificial intelligence is already a part of your daily life. Your phone uses it to schedule meetings movie recommendations, and dating apps use AI technology to facilitate meaningful connections.

Computer Vision and Artificial Intelligence have already improved how we approach tasks in our day-to-day workflows. The latest developments in this technology are improving by the day, and we are beginning to see it affect each element of our design and architecture process.

From generative design to AI analysis and 3D modeling, AI is becoming more and more integrated into the architecture.

And what does the future hold for A.I. technology, architecture, and design?

In an industry that’s barely touched by the digital era, artificial intelligence (or A.I.) is poised to change the architectural design and construction landscape. A.I. has already begun to transform the way architects design their workspaces and, most importantly, how they design/build their buildings.

Today, Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) is mainly associated with robotics and automobiles. But AI is also a promising technology in architecture and design. The future of A.I. technology in architecture and design will be far different than what sci-fi movies have portrayed. It will not manifest only as machines that look like humans and perform complex tasks. Instead, it will exist as a framework for quickly managing and performing large amounts of data.

Designers are used to working with tools that can generate new forms and shapes based on the rules we provide. Tools like Grasshopper, Dynamo, and others have been used for years to generate design from sets of rules. The next step is to give those rules so that a computer can understand them.

Artificial intelligence is a promising avenue for design and architecture. I think we will see its potential demonstrated in the coming years. As architects and designers, we need to be involved in this process, as users of the technology and creators of content for it.

Conclusion

The main advantage A.I. has over human designers and architects is the ability to analyze and understand information faster, with better precision and accuracy, and without bias or emotions.

While this makes it an effective tool for generating proposals and possibilities, certain aspects of architecture require judgment from humans: the integration of the building in its surroundings, its relationship to open space, the selection of materials and finishes, etc.

These are areas of architecture where A.I. may not yet be able to assist as much as we would want it to; however, giving it access to such a large number of possibilities will surely help us make more informed decisions.

Designing buildings is an art, architectural pedagogies and professional practices a science. Artificial intelligence (AI) is allied with the sciences, so it would seem natural to expect AI in the design and architecture professions. Maybe AI will use it to generate stories about how a building came to be. Or how AI is being used to write articles. Like this one!

This article was written with Copy.ai and the images made in dream by app.wombo.art .

Infrastructure and European Integration: a review of a few essays from the Journal History and Technology Vol. 27, No. 3 September 2011.

I have always found the link between illustration graphics and manifestos, power, and political views fascinating. Many of the most critical projects that have shaped the ideas and concepts in architectural discourse have not been built. However, their representation (drawings, models, and texts) has been critical in producing new paradigms in architectural design.

Borders and Infrastructure

In the special issue of History and Technology devoted to Infrastructural Europeanism, Schipper and Schot point out the importance of infrastructure in nation and region integration in Europe. The first intent for continent integration was in 1950 with the Coal and Steel Community, an organization with power beyond borders. The authors identify these attempts to construct a new Europe by building and administrating infrastructures across national borders. This notion of infrastructural globalism was a “project for permanent unified, world-scale institutional, technological complexes that generate globalist information not merely by accident, a by-product of other goals but by design” (Schipper & Schot, 2011). Moreover, the term “infrastructure” had to be re-defined and accepted beyond the standard French definition. By 1950 the word was part of the semantic dispute. One of its most vocal critics was Winston Churchill, who said, “The original authorship is obscure, but it may well be that these words’ infra and ‘supra’ have been introduced into our current political parlance by the band of intellectual highbrows who are naturally anxious to impress British labour with the fact that they learned Latin at Winchester.”

This rebuke did not prevail, and by 1960 the term referred to other non-material networks such as social and communication infrastructures. Historians explain that infrastructure created an imagined European community of transnational networks. It is relevant to point out that the emphasis on infrastructure making went beyond national or regional boundaries. It also dealt with global issues such as cross-border flows of people, goods, data, and energy. By 1990, Europe was a ‘zero-friction society’ with seamless mobility of capital, goods, people, and services. Today, this European seamless mobility is still limited to certain countries and excludes others, as in the case of some eastern European nations (Schipper & Schot, 2011).

The US/MX border region may have something to learn from the integration efforts of mid-twentieth-century Europe. Yet, there is a history of racism and xenophobia is still much alive in the territory. Across the American border region, some challenges might be resolved by shared or mutually conceived infrastructures. However, a difference from the European example is that the US/MX border region is a contested political space. More than an imaginary border or region (Anderson), it is a ‘real’ place with border actors (citizens, commerce, industry, etc.) and institutions creating binational policies. The border is a physical place and usually consists of cities from both countries coming together at the political division.

The lesson or questions are how a region of flows (people and goods) takes advantage of shared infrastructure, allowing regional sovereignty beyond the centralized visions of national capitals. The US/MX border cities are assemblages that can produce infrastructures capable of organizing social and technological infrastructure across borders.

Image, Technology, and History

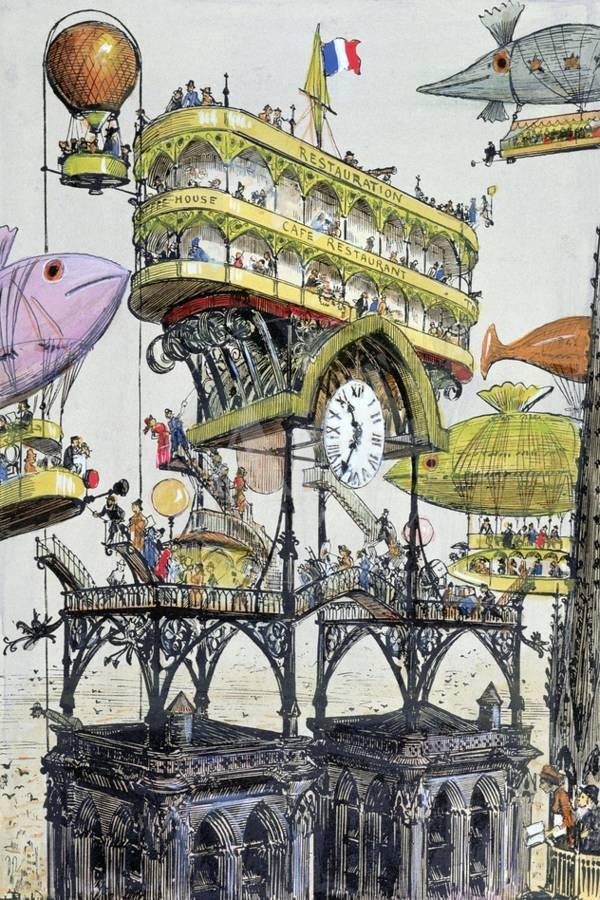

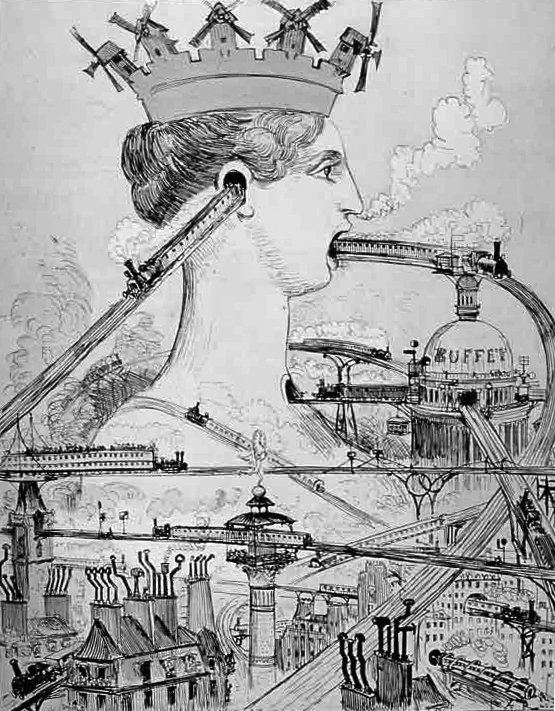

Images are a type of infrastructure; they communicate ideas, concepts, or the process of producing a design. They are powerful storytelling devices. Peter Soppelsa examines the cartoon or illustration of the Paris Metro by the French steampunk illustrator and science fiction novelist Albert Robida, published in 1886, portraying how the metro (railway system) might deform and violate the city “the queen city.” The author states, “It was a visual response to a visual problem” (Soppelsa, 2011). In opposition to the Haussmann metro project, a civil counter group was formed and led by Charles Garnier, a neoclassical architect known for designing the Paris Opera House. As a Neo classist Garnier looked at the past for inspiration and aesthetics, he produced significant buildings in Roman and Greek architecture. This form was fitting for elite buildings, signature pieces in the city. Therefore, his disdain for the metro was natural. He perceived structures and forms of steel as solely engineering. Infrastructure in a traditional sense must be invisible, undisruptive to the classical aesthetics of the city. In 1887, Garnier and a group of intellectuals launched an objection against the building of the Eiffel Tower, today a national symbol of France.

Very few cities today have a grand narrative. Infrastructure has been a driver of urban development, sustaining future growth based on demand, migration, labor dynamics, etc. The aesthetic of the postmodern city is one of collage and hybrid themes; there is no urban manifesto or Haussmanian hand that decides the future development or aesthetic of a city.

Images and concepts play an essential role in the marketing and politics of a city. Most cities have postcards with slogans and skylines that promote their economic attributes and urban lifestyles. Today, computer-generated images and models have become essential decision-making tools for government and communities. Through images, the public and policymakers can scrutinize a project (building or infrastructure) and its effect on a community by understanding its form, environmental impact, visual impression, and many other aesthetic and technical factors.

In the past decade, transportation infrastructure has been one of the major themes in urban development and resiliency projects. Along with urban strategies to safeguard and adapt to climate change, urban transportation, air travel, and personal mobility are now essential to planning projects that include housing, economic development, and public space. Max Hirsh evidences that images of infrastructure and technology are vital PR material for the developers and investors for project success and public acceptance (Hirsh, 2011). However, images of new and developing infrastructures tend to leave out the impact and variances that could occur as the general public appropriates these technologies. Within advertising images of services and goods, a particular user has a specific style of living or a suggested allure of transforming the user’s persona by its attainment. This is a common theme in the PR images of private developer condominiums towers in every major city. Buildings that search a specific market or try to create an appeal for a certain kind of living, most of the time the images are directed to upper-class citizens or private investors. This type of image advertising often steers a community into gentrification.

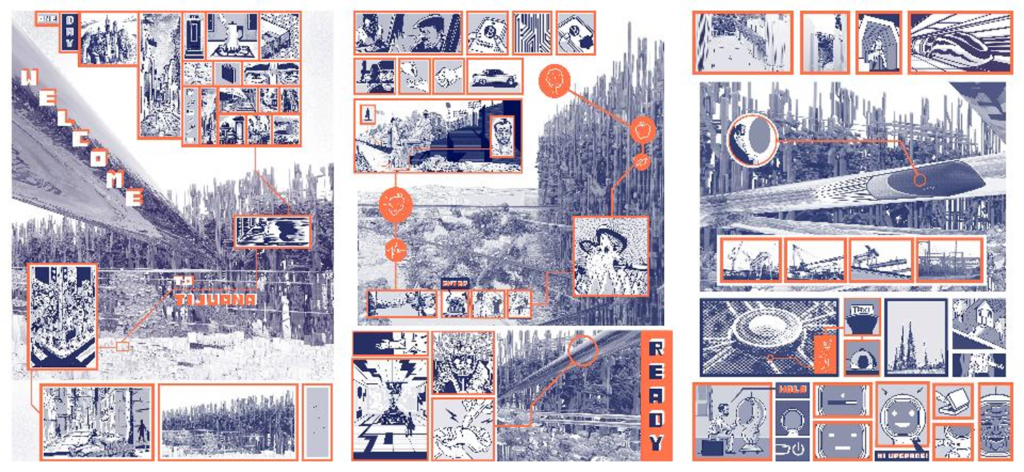

Max Hirsh concludes the text with two arguments. First, the typical user is absent from the official images and needs to be explicitly reintroduced. Therefore, instead of pictures of finished projects, a visual narrative based on a storyboard or comic strip can be helpful in the integration and understanding of infrastructure’s impact upon the broader public.

HyperloopMexa

In 2016 a team of colleagues and I developed a proposal for Hyperloop One, a cross-border system connecting Los Angeles, California, and Ensenada, Mexico. This technology uses a vacuum- tube system that would connect both cities in less than 20 minutes. An automobile journey takes approximately 4 hours, not including the wait at the international border. Currently, this technology is being developed by different private companies (Virgin Hyperloop, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, Hardt, among others), and all have invested in sophisticated PR images. Videos displaying how Hyperloop will change mobility and long-range transit in cities and regions where the system is implemented. However, the images presented display a system for a social class that is part of the business milieu who travel across regions and borders for business purposes. The pictures of the stations and transport pods are shown with the latest digital technology and stylized futuristic hygienic interiors. The future is always in white.

Our work in recent years has studied the realities of the places where the technology will operate, specifically in developing countries. As Max Hirsh points out, “Images provide scant information about how they operate in practice; or about how infrastructure systems, once built, are subsequently appropriated by their users and reconfigured to meet shifting political and economic demands” (Hirsh, 2011). Hyperloop technology images do not show or illustrate how the rest of the population will use and be affected by this disruptive transportation technology. We argued that workers in low-paying jobs such as in the hotel cleaning service, fast food service, landscaping, construction, among others, would be the frequent use of the system and not the Caucasian business class passengers that appear in the PR images. The narrative in the advertising for the system demonstrates a seamless integration between multimodal mobility infrastructure (tubes, stations, buses, etc.) within the urban fabric. However, we argue that as these technologies hit the ground, they will displace or be in conflict with traditional and stable private/public transport systems such as taxis, buses, and other modalities that operate organically in developing countries. New Technologies also discriminate against those who cannot pay for its service through images of social class hierarchies.

Works Cited

Hirsh, M. (2011). What’s missing from this picture? Using visual materials in Infrastructure studies. History and Technology, 379-387.

Schipper, F., & Schot, J. (2011). Infrastructural Europeanism. History and Technology, 245-264.

Soppelsa, P. (2011). Visualizing viaducts in 1880s Paris. History and Technology, 371-377.

Hola a todos. Ya tenemos la libreta Building Tijuana con hoja cuadriculada (130 pg). De buen tamaño para cargar en bolsillo y plasmar esas grandes ideas sobre arquitectura, diseño, arte, etc. Se pueden comprar por Amazon

Hello everyone. We now have the Building Tijuana notebook with grid sheets (130 pg). Good size to carry in your pocket and capture those great ideas about architecture, design, art, etc. Makes a great gift! You can buy it on Amazon

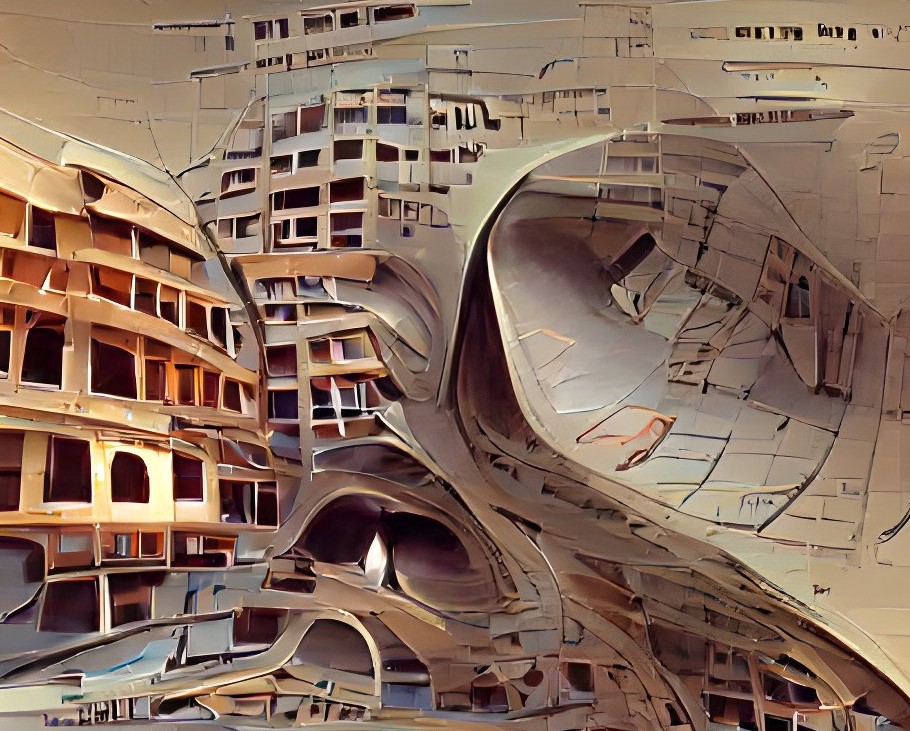

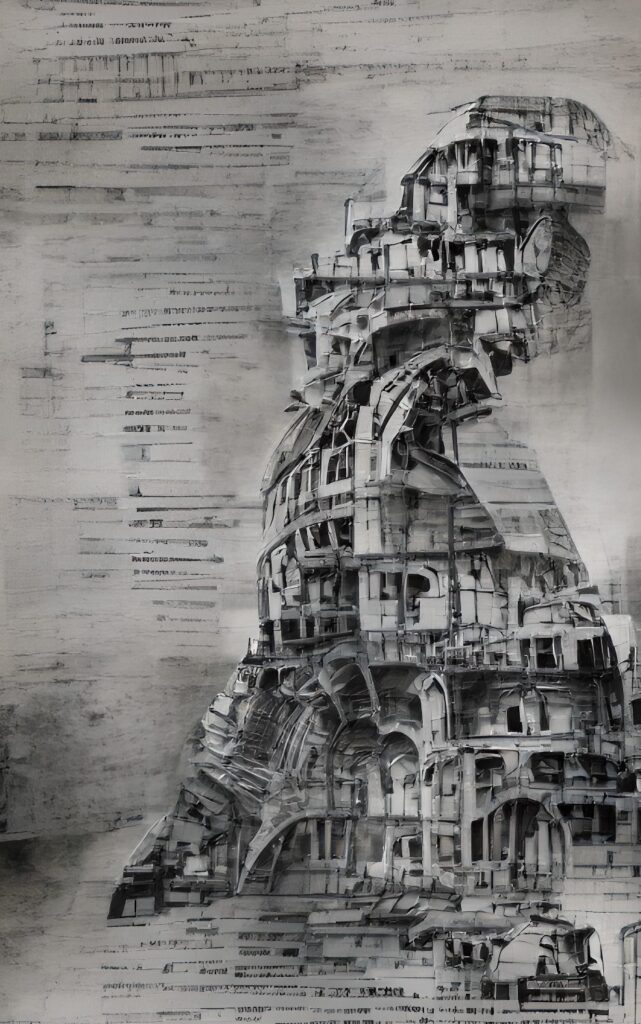

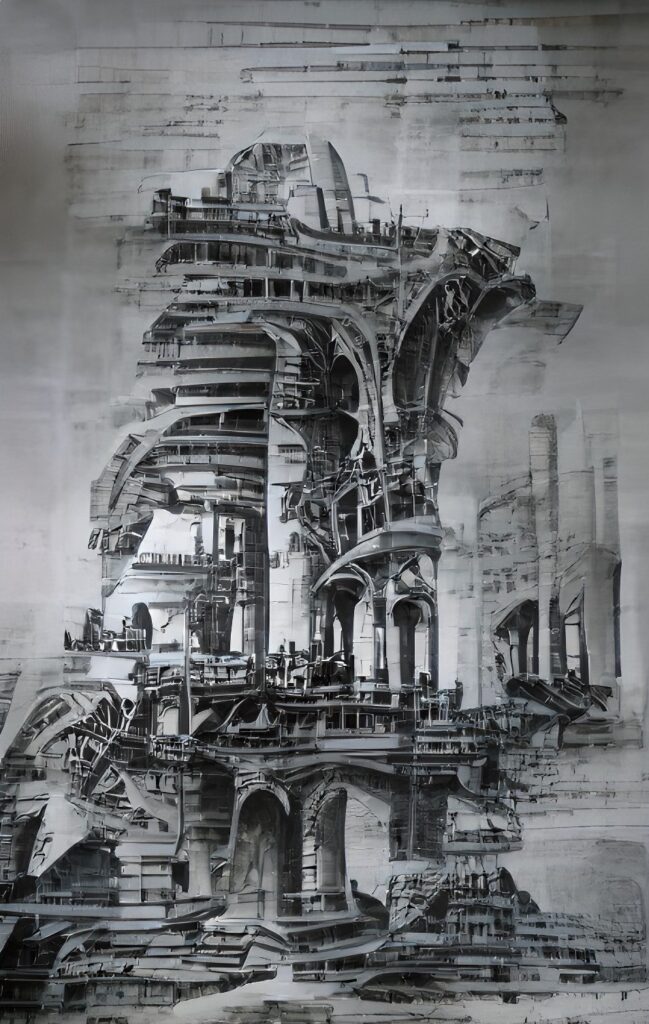

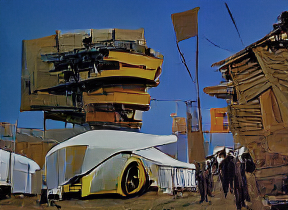

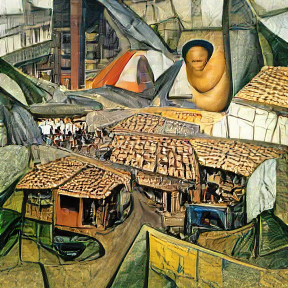

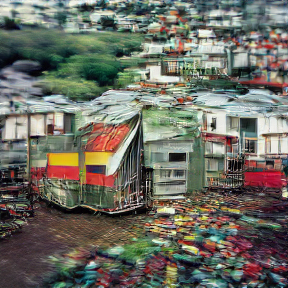

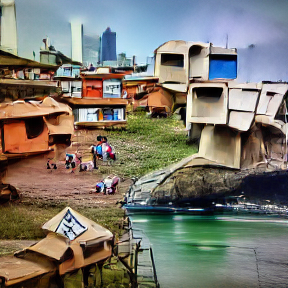

These days I am experimenting with some sites that use neural networks or artificial intelligence as they call it to create images based on text. In the first image, I typed words that had to do with the informal city and Syd Mead’s graphics. This is what the neural network created after 2000 iterations.

If you want to create some images yourself here is the link to the Ai page. https://colab.research.google.com/…/1lx9AGsrh7MlyJhK9Ur…

The shantytowns of Latin America are the future of cities. Oil painting by Diego Rivera

In the background, the city crouching on distant hills dissipating under a gray mist of a cold morning. There is no sign or sigh of human life. Painting by HG Giger

The shantytowns of Latin America are the future of cities. oil painting. By Mobius

The shantytowns of Latin America are the future of cities. By Gerhard Richter

The shantytowns of Latin America are the future of cities. By Le Corbusier

The shantytowns of Latin America are the future of cities. By Gaudi

Quiero felicitar a Monica Arreola, arquitecta y artista Tijuanense por su inclusión en la Whitney Bienal del 2022 con su proyecto desinterés social.

I would like to congratulate Monica Arreola, architect, and artist from Tijuana for her selection to the Whitney Biennial 2022 with her project “desinterés social”.

Para ver la obra / To see the project: https://www.monicaarreola.com/desinteres-social

https://whitney.org/exhibitions/2022-biennial

Aquí un breve texto sobre una de las fotografías de Arreola . Here is a brief text reagarding one of Arreola’s photographs.

This photograph hides nothing. The photograph makes visible the absence of a home. Three rectangular structures of derelict or still borne houses are centered in the composition, each with two dark square openings as if staring back at the viewer. In the foreground, a landscape of dead lawn patches and a few invasive greeneries create a datum for the aborted homes. In the background, the city crouching on distant hills dissipating under a gray mist of a cold morning. There is no sign or sigh of human life. The landscape is desolate. The only fragment of urbanity is a semi-finished perimeter wall of an adjacent gated community displaying a couple of insipid graffiti tags.

The camera angle frames a one-point perspective, an architectural graphic device, and a virtual view of the world, unlike how we see with our own eyes. By looking at the image, we do not know why the photographer used that point of view. There is no accurate way to be in a place. However, I cannot seem to divert my attention from the writing on the walls, the scribble of signs or words in black outlines, and others in faint orange. Tagged with no apparent order, nevertheless widespread on the surface to produce an aesthetic mood of the objects. The photo also has cumulus clouds!

Rene Peralta

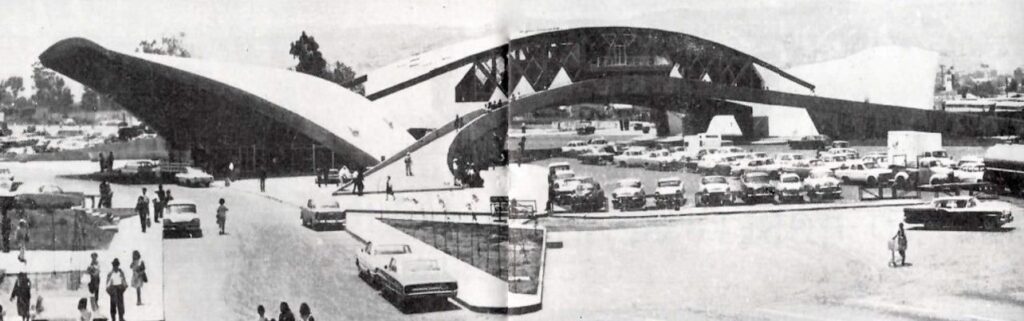

The hybrid structure, part bridge and part building flanked by two large paraboloids made of concrete housed the immigration offices of the Mexican government. It was colloquially known as “la concha” or the seashell to all who waited in line to cross into the US via the San Ysidro Port of Entry in Tijuana. The building was abandoned, uncared-for during its last years, and finally demolished in 2015. As Alejandra Lange points out, critics sometimes have to step into the role of activist (Lange, 2012), and when I found out that the federal government wanted to demolish the structure, I did. I joined others in the struggle to preserve the building. Historians, attorneys, artists, and the general public held live debates near the building to show solidarity for one of the last modernist buildings left in the city.

The building mattered because it complied with two of Riegl’s categories, use-value and newness value (Riegl, 1982). However, it was also a signature of Mexican modernism and paraboloid concrete construction made famous by Felix Candela. La Concha was a testament that there was a time when Mexico and Tijuana wanted to be modern. The building was not only a magnificent building but part of a more significant project, the modernization of ports of entry in Mexican border cities. Architect Mario Pani directed the federal initiative known as the Border National Project of 1965 and oversaw most of the design and construction for the country’s modern open land ports.

Lange, A. (2012). Writing About Architecture: Mastering the Language of Building and Cities. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Riegl, A. (1982). The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin. Oppositions 25, 21-51.

As we analyze 20th-century global empire building, we must consider distinct actors in addition to hegemonic nation-states that challenged physical systems, organizational and political infrastructures, market-driven economies, and other drivers of national and regional sovereignty. In Large Technological Systems (LTS), such as shipping and rail infrastructure, there is a second layer of global private/public relationships apart from international agreements within national and global stations, ports, and networks.

Indecorous Concessions. In the article, The Suez Company’s Concession in Egypt, 1854—1956: Modern Infrastructure and Local Economic Development, Caroline Piquet demonstrates the transformation of the Suez Canal from a colonial LTS infrastructure into a symbol for Egyptian national independence.

Soeren Stache/picture alliance/Getty Image

The struggle by Egypt for control, management, and operation of the Suez Canal was part of the confrontation to re-possess one of the most extensive and expensive canals of its time. Built-in 1869, it was one of the world’s most extensive canals, creating economic value favoring shareholders in Europe. During the 20th century, the canal was a contested infrastructural landscape, and in 1956, Egypt took control and began to operate the canal.

Since its construction, the training in complex technical knowledge for the canal’s operation was reserved for European engineers, and local Egyptian workers were trained for low-skill operations. However, the canal’s nationalization was a successful event, and its subsequent operation was a profitable one. “The canal belongs to Egypt and not Egypt to the canal” (Piquet, 2004) . The Suez became an essential asset for the economy and sovereignty of the country.

For over 100 years, the canal was an infrastructure in a country that did not benefit from its operation. As a concession, the investment was made to favor European capital. As Piquet writes, “Thus the concession system appears less as an instrument for the spread of global capitalism to all nations, and more as a tainted for of “colonial” capitalism” (Piquet, 2004).

Time is on my side, yes it is. In Jules Verne’s famous novel Around the World in Eighty Days, the principal character Phileas Fogg uses countless modes of transportation to travel around the world. Phileas Fogg is the modern subject, the universal man that navigates the globe, and in every place he visits, there is a possibility of movement. No matter how primitive the system is, his journey becomes part of a larger global mobility culture. Fogg is interconnected with global time and its dramas, psychologies, and stress of a soon-to-be globalized planet. “In this sense, the novel is a technology for the imagining of people’s synchronization in time (Grossman, 2013).

The organization of something so abstract as time is the driving metric of modernity. We no longer arrange daily life based on the sun’s path. We reorganize schedules and tasks according to efficiency, costs, markets, and production. Transportation linked to labor and markets is part of the time machine that modern man must always be aware of. In Verne’s novel, time becomes the main character, even more, critical than Fogg’s journey. Time is always ahead, apparent, and a force to be reckoned with. Verne makes time reckoning more rapidly and is scripted. “The novel – which significantly loses in its English titling that ‘Le tour du monde.’ also means the turning of the earth – spilled quite directly over into this historical context. Four months after its publication, Verne addressed the French Geographic Society on the question of which meridian should be chosen for travelers to separate one calendar day from another worldwide” (Grossman, 2013).

Eleven years later, the world accorded how to measure and keep time around the globe.

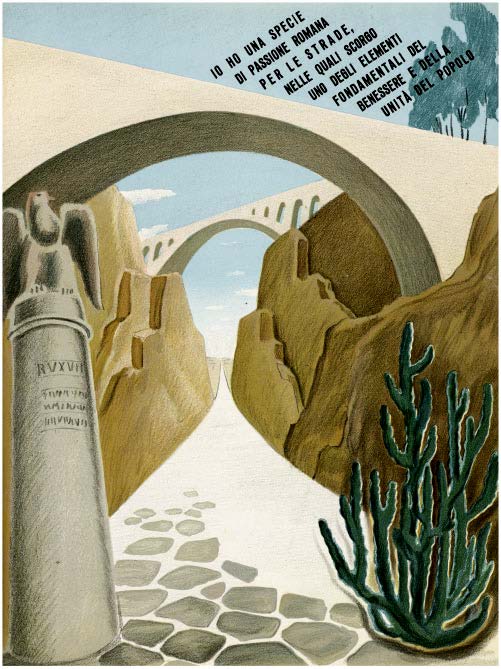

Il Duce’s Way. The road-building projects set out by the Italian Fascist in Africa were as much propaganda as critical infrastructure. As Roland Barthes describes, if it was crucial, it relied on the ability to be photographed as a connoted message of empire-building and infrastructures. According to Andrew Denning, “Such audacious roadworks demonstrated an essential claim of Mussolini’s fascist movement: that Il Duce’s regime had accepted the inheritance of ancient Rome but had updated it with the Italian mastery of modern technology. Roads were timeless forms of imperial power and manifestations of fascist modernity simultaneously” (Denning, 2020). The aesthetic ideology found in Mussolini’s aspiration of colonial empire seems to originate via the Italian Avant-garde of the early 20th century. This display of contemporary technology echoes the sentiment of the Italian Futurist, specifically its leader and manifesto author Filippo Marinetti.

Italian Futurism proposed an aesthetic of speed—a movement absorbed by the machine, precisely the automobile in all its violence and terror. Machines and war were part of the allure of violence that the Futurist needed, and the desire to participate in militarization acts as an aesthetic project. New ways of moving and being in the world concerning time/speed became part of a new “machine” sentiment that included a no-return to tradition and histories before the industrial turn of European society.

It is this aesthetic lure with machines, speed, and war that the futurists see as the potential in the fascist project. In Politics as Art: Italian Futurism and Fascism, Anne Bowler explains, “This nonhuman and mechanical being, constructed for an omnipresent velocity, will be naturally cruel, omniscient, and combative” (Bowler, 1991). For Marinetti and the Futurist group, who actively campaigned and subsequently fought for Italy’s intervention in the war and the coming to power of Mussolini and the Fasci di Combattimento, the dictator represented the ultimate triumph of the Futurist-Fascist revolution that Marinetti envisioned under the direction of a new “proletariat of geniuses,” an elite cadre of Futurist artists and intellectuals.” However, For Marinetti, Art was no longer tied to its Roman history, and he denounced any past link or precedent. Art was a transcendental endeavor to create a new nationalism and morality based on technology (Bowler, 1991).

Road-building was a way to modernize the colonial ideals and prepare society for technologies or machines that would change the time-space primitive environment. Italians fetishized technology in a way that produced an aesthetic and political zeitgeist for most of the early 20th century.

Denning said, “Roads were timeless forms of imperial power and manifestations of fascist modernity simultaneously “ (Denning, 2019).

Miami Beach, Florida, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection, XB1990.587. Photo: David Almeida.

References

Bowler, A. (1991). Politics as Art: Italian Futurism and Fascism. Theory and Society, 763-794.

Denning, A. (2019). Infrastructural Propaganda: The Visual Culture of Colonial Roads and the Dosmitication of Nature in Italian East Africa. American Society for Environmental History and Forest History Society, 352-369.

Grossman, J. H. (2013). The Character of global transport infrastructure: Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days. History and Technology, 247-261.

Piquet, C. (2004). The Suez Company’s Concession in Egypt, 1854-1956: Modern Infrastructure and Local Economic Development. Enterprise and Society. Vol. 5 No.1, 107-127.